German Enlightenment

The German Enlightenment[a] (German: die deutsche Aufklärung)[2] refers to the intellectual and cultural movement that flourished in the 18th-century German states as part of the broader Enlightenment (historically known in German as die Aufklärung).

Prussia took the lead among the German states in sponsoring the political reforms that Enlightenment thinkers urged absolute rulers to adopt. There were important movements as well in the smaller states of Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, and the Palatinate, although the Protestant regions were globally more active in the German Enlightenment than the Catholic ones. In each case, Enlightenment values became accepted and led to significant political and administrative reforms that laid the groundwork for the creation of modern states.[3]

The recognition and application of Enlightenment cultural, intellectual and spiritual ideals and standards led to a flourishing of art, music, philosophy, science and literature in the German states. The German Enlightenment differed somewhat from the French Enlightenment: "Whereas the French philosophes often took a violently anticlerical and combative tone, their German counterparts avoided direct confrontations with authorities",[4] even though "French anti-clericalism briefly dominated German Enlightenment thought".[5]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1685, Margrave Frederick William of Prussia issued the Edict of Potsdam within a week after French king Louis XIV's Edict of Fontainebleau, that decreed the abolishment of the 1598 Edict of Nantes which had conceded to free religious practice for Huguenots. Frederick William offered his "co-religionists, who are oppressed and assailed for the sake of the Holy Gospel and its pure doctrine...a secure and free refuge in all Our Lands".[6] Around 20,000 Huguenot refugees arrived in an immediate wave and settled in the cities, 40% in Berlin, the ducal residence alone. The French Lyceum in Berlin was established in 1689 and the French language had by the end of the 17th century replaced Latin to be spoken universally in international diplomacy. The nobility and the educated middle-class of Prussia and the various German states increasingly used the French language in public conversation in combination with universal cultivated manners.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Prussia had therefore access, like no other German state, to the skill set for the application of pan-European Enlightenment ideas to develop more rational political and administrative institutions.[7] The princes of Saxony would carry out a comprehensive series of fundamental fiscal, administrative, judicial, educational, cultural and general economic reforms. The reforms were aided by the country's strong urban structure and influential commercial groups, who would modernize pre-1789 Saxony along the lines of classic Enlightenment principles.[8]

Early phase

[edit]The Enlightenment gradually transformed German high culture in a variety of fields: literature, music, philosophy, and science.

The German Enlightenment "supposedly" began with Christian Thomasius.[9] The polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was "in the vanguard of the German Enlightenment".[10] The philosopher Christian Wolff expounded the Enlightenment to German readers and established German as the prevailing language of philosophical reasoning, scholarly instruction and research.[11]

During the first half of the 18th century, German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under Johann Sebastian Bach.[12]

In 1740, Frederick the Great began to rule Prussia, and would do so until his death in 1786. As worded by Elizabeth Haller Ellis, Frederick was "less an enlightened ruler than a despotic patron of enlightenment culture".[13]

High phase

[edit]From approximately the mid-18th century to the 1770s was the phase of “High German Enlightenment”.

In 1755, the young Immanuel Kant from Königsberg published Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens. The same year, the first German bourgeois tragedy, Miss Sara Sampson, by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, was premiered. Between 1767 and 1769, Lessing would also write Hamburg Dramaturgy, an important collection of essays about theater. He was at that time employed by the theatre principal Abel Seyler, who greatly influenced the development of German theatre and promoted serious German opera, new works and experimental productions, and the concept of a national theatre.[14] German music would continue flourishing in the second half of the 18th century with Christoph Willibald Gluck, Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[15]

Late phase

[edit]In 1770, Kant introduced a new theory about metaphysics in his inaugural dissertation on the occasion of his appointment as professor of metaphysics at the University of Königsberg.

In the 1770s, Johann Gottfried Herder broke new ground in philosophy and poetry, as a leader of the Sturm und Drang, a precursor to Romanticism. In 1779, Lessing completed Nathan the Wise, a play on religious tolerance, which would only be premiered after his death.

From the 1780s to the early 1800s, a cultural and literary movement based in Weimar, the Weimar Classicism, sought to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical, and Enlightenment ideas; the movement involved Herder as well as polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, a poet and historian. Herder argued that every group of people had its own particular identity, which was expressed in its language and culture. This legitimized the promotion of German language and culture and helped shape the development of German nationalism. Schiller's plays expressed the restless spirit of his generation, depicting the hero's struggle against social pressures and the force of destiny.[16]

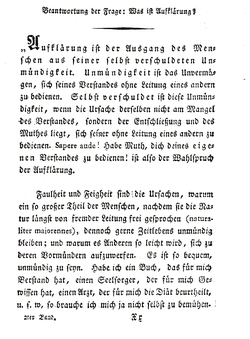

In remote Königsberg, an older Kant tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom, and political authority, completing his Critique of Pure Reason in 1781, and his essay What Is Enlightenment? in 1784. Kant's late works contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought—and indeed all of European philosophy—well into the 20th century.[17]

Limits

[edit]German Enlightenment won the support of princes, aristocrats, and the middle classes, and it permanently reshaped the culture.[18] However, there was a conservatism among the elites that warned against going too far.[19] In 1788, Prussia issued an "Edict on Religion" that forbade preaching any sermon that undermined popular belief in the Holy Trinity or the Bible. The goal was to avoid theological disputes that might impinge on domestic tranquility. Men who doubted the value of Enlightenment favoured the measure, but so too did many supporters. German universities had created a closed elite that could debate controversial issues among themselves, but spreading them to the public was seen as too risky. This intellectual elite was favoured by the state, but that might be reversed if the process of the Enlightenment proved politically or socially destabilizing.[20]

End

[edit]The Napoleonic Wars brought an end to the German Enlightenment and gave rise to German Romanticism.

By center

[edit]Berlin Enlightenment

[edit]The Berlin Enlightenment flourished under Frederick the Great.

Königsberg Enlightenment

[edit]The Königsberg Enlightenment was centered in the city of Königsberg in East Prussia, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia. Key Königsberg enlighteners include Immanuel Kant and Christian Jakob Kraus. The University of Königsberg was a major hub of Enlightenment activity.

Bavarian Enlightenment

[edit]The key figure of the Bavarian Enlightenment was Lorenz von Westenrieder.[21]

Influence on other enlightenments

[edit]The German Enlightenment influenced both the Austrian and Jewish Enlightenments—though each developed under distinct conditions.

Austrian Enlightenment

[edit]Many Austrian thinkers were influenced by German ideas, but the Austrian Enlightenment was more pragmatic, Catholic, and authoritarian than the more theoretical and philosophical German one.

In his work about the Austrian Enlightenment, Ernst Wangermann distinguished, on one hand, the point of view of conservative Catholic historians, for whom the Enlightenment had been something completely alien to the real Austrian traditions, as something which had been imported from outside and had been anti-Catholic; and, on the other hand, the point of view of liberal and anti-clerical historians who, in light of the concept of Greater Germany, considered the Austrian Enlightenment to have been a pale reflection or an imitation of the German Enlightenment.[22]

Jewish Enlightenment

[edit]The German Enlightenment influenced the Jewish Enlightenment known as the Haskalah.

See also

[edit]- Gleimhaus, museum of the German Enlightenment in Halberstadt, Germany

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sheehan 1989, p. 175.

- ^

- ^ Charles W. Ingrao, "A Pre-Revolutionary Sonderweg." German History 20#3 (2002), pp. 279–286.

- ^ The Making of the West. 2009. p. 565.

- ^ Schleiermacher and Palmer. 2019.

- ^ "Edict of Potsdam, October 29, 1685". Deutsche Geschichte in Quellen und Darstellung. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Charles W. Ingrao, "A Pre-Revolutionary Sonderweg". German History 20#3 (2002), pp. 279–286.

- ^ Katrin Keller, "Saxony: Rétablissement and Enlightened Absolutism". German History 20.3 (2002): 309–331.

- ^ Mulsow 2023, p. 1.

- ^ Newman, Lindsay Mary (1966). Leibniz (1646–1716) and the German Library Scene. p. 36.

- ^ Gagliardo, John G. (1991). Germany under the Old Regime, 1600–1790. pp. 217–234, 375–395.

- ^ Owens, Samantha; Reul, Barbara M.; Stockigt, Janice B., eds. (2011). Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities.

- ^ Ellis, Elizabeth Haller (1999). The Judging Public. p. 39.

- ^ Kosch 2005, p. 308.

- ^ Owens, Samantha; Reul, Barbara M.; Stockigt, Janice B., eds. (2011). Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities.

- ^ Richter, Simon J., ed. (2005), The Literature of Weimar Classicism

- ^ Kuehn, Manfred (2001). Kant: A Biography.

- ^ Van Dulmen, Richard; Williams, Anthony, eds. (1992). The Society of the Enlightenment: The Rise of the Middle Class and Enlightenment Culture in Germany.

- ^ Thomas P. Saine, The Problem of Being Modern, or the German Pursuit of Enlightenment from Leibniz to the French Revolution (1997)

- ^ Michael J. Sauter, "The Enlightenment on trial: state service and social discipline in eighteenth-century Germany's public sphere." Modern Intellectual History 5.2 (2008): 195–223.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. 2013. p. 605.

- ^ Le Règne de Charles III (in French). 1994. p. 155.

Sources

[edit]- Annen, Martin (1997). Das Problem der Wahrhaftigkeit in der Philosophie der deutschen Aufklärung (in German).

- Brüggemann, Fritz (1972) [1928]. Aus der Frühzeit der deutschen Aufklärung: Christian Thomasius und Christian Weise (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 3-534-02914-3.

- Kosch, Wilhelm (2005). "Seyler, Abel". In Killy, Walther; Vierhaus, Rudolf (eds.). Dictionary of German Biography. Vol. 9. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-096629-9.

- Kronauer, Ulrich; Garber, Jörn, eds. (2001). Recht und Sprache in der deutschen Aufklärung (in German). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Mulsow, Martin (2023). The Hidden Origins of the German Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press.

- Pütz, Peter [in German] (1991) [1978]. Die deutsche Aufklärung (in German). Darmstadt. ISBN 3-534-06092-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sheehan, James J. (1989). German History, 1770–1866.

Further reading

[edit]- Ahnert, Thomas (2006). Religion and the Origins of the German Enlightenment: Faith and the Reform of Learning in the Thought of Christian Thomasius. University of Rochester Press.

- Ahnert, Thomas; Décultot, Elisabeth; Grote, Simon; Michelangelo-D'Aprile, Iwan; Lifschitz, Avi (2017). "The German Enlightenment". German History. 35 (4): 588–602. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghx104.

- Fillafer, Franz Leander; Osterhammel, Jürgen (2012). "Cosmopolitanism and the German Enlightenment". The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History. p. 119–143. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199237395.013.0006.

- Pope, Timothy (1986). "The German Enlightenment: Literaturgeschichte or Theologiegeschichte". Man and Nature. 5: 153–163. doi:10.7202/1011859ar.

- Reill, Peter Hanns (1975). The German Enlightenment and the Rise of Historicism. University of California Press.

- Sumser, Robert (1992). "Erziehung, the Family, and the Regulation of Sexuality in the Late German Enlightenment". German Studies Review. 15 (3). doi:10.2307/1430362. JSTOR 1430362.

- Vermeulen, Han F. (2015). Before Boas: The Genesis of Ethnography and Ethnology in the German Enlightenment. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803255425.