Demographic transition

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Demographic transition is a phenomenon and theory in the social sciences (especially demography) referring to the historical shift from high to low rates of birth and death, as societies attain several attributes: more technology, education (especially for women), and economic development.[1] The demographic transition has occurred in most of the world over the past two centuries, bringing the unprecedented population growth of the post-Malthusian period, and then reducing birth rates and population growth significantly in all regions of the world. The demographic transition strengthens the economic growth process through three changes: reduced dilution of capital and land stock; increased investment in human capital; and increased size of the labor force relative to the total population, along with a changed distribution of population age.[2] Although this shift has occurred in many industrialized countries, the theory and model are often imprecise when applied to individual countries, because of specific social, political, and economic factors that affect particular populations.[1]

Nevertheless, the existence of some type of demographic transition is widely accepted because of the well-established historical correlation between two factors: dropping fertility rates, and social and economic development.[3] Scholars debate whether industrialization and higher incomes lead to lower population, or vice versa. Scholars also debate to what extent various proposed and sometimes interrelated factors are involved—factors such as higher per capita income, lower mortality, old-age security, and increased demand for human capital.[4] Human capital gradually increased during the second stage of the Industrial Revolution, which coincided with the demographic transition. The increasing role of human capital in the production process led families to invest this capital in children, which may have been the beginning of the demographic transition.[5]

History

[edit]This theory is based on an interpretation of demographic history developed in 1930 by the American demographer Warren Thompson (1887–1973).[6] Adolphe Landry of France made similar observations on demographic patterns and population growth potential around 1934.[7] In the 1940s and 1950s, Frank W. Notestein developed a more formal theory of demographic transition.[8] In the 2000s, Oded Galor researched the "various mechanisms that have been proposed as possible triggers for the demographic transition, assessing their empirical validity, and their potential role in the transition from stagnation to growth."[5] In 2011, the unified growth theory was completed, and the demographic transition became an important part of this theory.[2] By 2009, the existence of a negative correlation between fertility and industrial development had become one of the most widely accepted findings in social science.[3]

The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia were among the first populations to experience a demographic transition, during the 18th century, before changes in mortality or fertility with other European Jews or with Christians living in the Czech lands.[9] The demographer John Caldwell explained that fertility rates in the Third World do not depend on the spread of industrialization or even on economic development; he also showed that fertility decline is more likely to precede and facilitate industrialization than to follow it.[10]

Overview

[edit]

The demographic transition involves four stages, or possibly five.

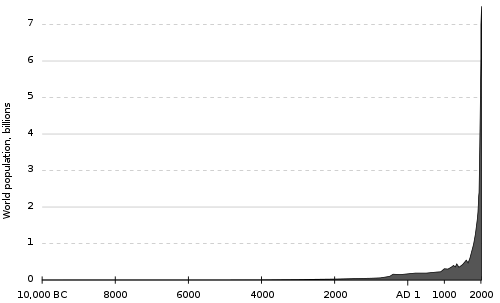

- In Stage 1, that of pre-industrial society, death rates and birth rates are high and roughly in balance. All human populations are believed to have had this balance until the late 18th century, when it ended in Western Europe.[11] In fact, growth rates were less than 0.05% since at least the Agricultural Revolution, more than 10,000 years ago.[11] Population growth is typically very slow during this stage because society is constrained by the available food supply; therefore, unless society develops new technologies to increase food production (e.g., discovers new sources of food, or achieves higher crop yields), any fluctuation in birth rates is soon matched by death rates.

- In Stage 2, that of a developing country, death rates quickly drop because of improvements in food supply and sanitation, which increase life expectancy and reduce disease. Improvements specific to food supply typically include selective breeding, in addition to crop rotation and farming techniques.[11] Numerous improvements in public health reduce mortality, especially for children.[11] Before the mid-20th century, these improvements in public health primarily concerned food handling, water supply, sewage, and personal hygiene.[11] An often-cited variable is the increase in female literacy, in combination with public-health education programs that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[11] In Europe, the decline in death rates started in the late 18th century in northwestern Europe, and it spread to the south and east over approximately the next 100 years.[11] Without a corresponding fall in birth rates, this change produces an imbalance, and countries in this stage experience a large increase in population.

- In Stage 3, birth rates fall because of various fertility factors, such as the following: access to contraception; increases in wages; urbanization; a reduction in subsistence agriculture; an increase in the status and education of women; a reduction in the value of children's work; an increase in parental investment in the education of children; and other social changes. Population growth begins to level off. The birth-rate decline in developed countries started in the late 19th century in Northern Europe.[11] While improvements in contraception play a role in birth-rate decline, contraceptives were not generally available nor widely used in the 19th century. As a result, they likely played an insignificant role in the decline at that time.[11] Birth-rate decline is also caused by a transition in values, not just the availability of contraceptives.[11]

- In Stage 4, birth and death rates are both low. Birth rates may drop to well below replacement level, as has happened in countries such as Germany, Italy, and Japan; this drop leads to a shrinking population, which threatens many industries that rely on population growth. As the large group born during Stage 2 ages, an economic burden is placed on the shrinking working population. Death rates may remain consistently low or increase slightly because of increases in lifestyle diseases due to several factors: low exercise levels, high obesity rates, and an aging population in developed countries. By the late 20th century, birth rates and death rates in developed countries had leveled off at lower rates.[12]

- A "Stage 5" is broken out from Stage 4 by some scholars, with below-replacement fertility levels. Other scholars hypothesize a different "Stage 5" involving an increase in fertility.[13]

As with all models, the Demographic Transition Model (DTM) is an idealized picture of population change in these countries. The model is a generalization that applies to these countries as a group, and it may not accurately describe each specific case. The extent to which the model applies to less-developed societies remains to be seen. Many countries—such as China, Brazil, and Thailand—have passed through the DTM very quickly because of rapid social and economic change. Some countries, particularly in Africa, appear to be stalled in the second stage because of stagnant development, as well as the effects of insufficient investment and research into tropical diseases such as malaria and AIDS, to some extent.

Stages

[edit]Stage 1

[edit]In pre-industrial society, death rates and birth rates were both high—fluctuating rapidly according to natural events, such as drought and disease, to produce a relatively constant and young population.[1] Family planning and contraception were virtually nonexistent; therefore, birth rates were essentially limited only by the ability of women to bear children. Emigration depressed death rates in some special cases (for example, Europe and particularly the eastern United States during the 19th century). But overall, death rates tended to match birth rates, often exceeding 40 per 1000 per year. Children contributed to the household's economy from an early age in multiple ways: carrying water, firewood, and messages; caring for younger siblings; sweeping; washing dishes; preparing food; and working in the fields.[14] Raising a child cost little more than feeding them; there were no education or entertainment expenses. Thus, the total cost of raising children barely exceeded their contribution to the household. Moreover, as children grew into adulthood, they became a major input to the family business, mainly farming; they were also the primary form of insurance for adults in old age. In India, an adult son was frequently the only thing that prevented a widow from falling into destitution. While death rates remained high, there was no question about the need for children, even if a means to prevent their birth had existed.[15]

During this stage, society evolves in accordance with the Malthusian paradigm, with population essentially determined by the food supply. Any fluctuations in food supply—either positive, for example, because of technology improvements, or negative, due to droughts and pest invasions—tend to translate directly into population fluctuations. Famines resulting in significant mortality are frequent. Overall, population dynamics during Stage 1 are comparable to those of animals living in the wild. This is the earlier stage of the demographic transition in the world; it is also characterized by primary activities such as small-scale fishing, farming practices, pastoralism, and small businesses.

Stage 2

[edit]

This stage leads to a fall in death rates and an increase in population.[16] The changes leading to this stage in Europe were initiated during the Agricultural Revolution of the eighteenth century, and they were initially quite slow. In the twentieth century, the declines in death rates in developing countries tended to be substantially faster. Countries in this stage include Yemen, Afghanistan, Iraq, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa (but not South Africa, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, Gabon, and Ghana, which have begun to move into Stage 3).[17][needs update]

The decline in death rates is initially due to two factors:

- Improvements in the food supply—brought about by higher yields in agricultural practices and better transportation—reduce death due to starvation and lack of water. Agricultural improvements include crop rotation, selective breeding, and seed drill technology.

- Significant improvements in public health reduce mortality, particularly in childhood. These improvements are not primarily medical breakthroughs. For example, Europe passed through Stage 2 before the medical advances of the mid-twentieth century, although there was significant medical progress during the 19th century, such as the development of vaccination. Rather, they are primarily improvements in water supply, sewage, food handling, and general personal hygiene. Hygiene, in particular, improved through growing scientific knowledge about the causes of disease, as well as improved education and social status for mothers.

As a consequence of the decline in mortality during Stage 2, population growth is increasingly rapid (a.k.a. a population explosion), as the gap between death rates and birth rates continually widens. This growth is not due to an increase in fertility (or birth rates) but to a decline in deaths. This population change occurred in northwestern Europe during the 19th century because of the Industrial Revolution. During the second half of the twentieth century, less-developed countries entered Stage 2, creating a rapid worldwide increase in population that causes demographers to be concerned today. In this stage of demographic transition, countries are vulnerable to becoming failed states in the absence of progressive governments.

Another characteristic of Stage 2 is a change in the age structure of a population. In Stage 1, the majority of deaths are concentrated in the first 5–10 years of life. For this reason, the decline in death rates in Stage 2 involves the increasing survival of children and a growing overall population. Hence, the age structure of the population becomes increasingly youthful; people begin to have large families, and more of these children enter the reproductive period of their lives while maintaining the high fertility rates of their parents. The bottom of the population pyramid—where infants, children, and teenagers are located—widens first, accelerating population growth rate. The age structure of such a population can be illustrated by using an example from the Third World today.

Stage 3

[edit]

In Stage 3 of the Demographic Transition Model, death rates are low, and birth rates diminish, generally as a result of several factors: enhanced economic conditions; expansion of women's status and education; and access to contraception. The decrease in birth rate fluctuates from nation to nation, as does the time span during which it is experienced.[18] Stage 3 moves the population towards stability through a decline in birth rate.[19] Several fertility factors contribute to this eventual decline, and these factors generally resemble those associated with sub-replacement fertility, although some factors are speculative:

- In rural areas, a continued decline in childhood deaths implies that, at some point, parents realize that they do not need as many children to ensure a comfortable old age. As childhood deaths continue to fall and incomes increase, parents can become increasingly confident that fewer children will suffice to help with family business and care for them in old age.

- Increasing urbanization changes the traditional value placed upon fertility, as well as children in a rural society. Urban living also raises a family's costs for dependent children. A recent theory suggests that urbanization also contributes to reducing the birth rate, because it disrupts optimal mating patterns. A 2008 study in Iceland found that the most fecund marriages are between distant cousins. Genetic incompatibilities inherent in more distant outbreeding make reproduction more difficult.[20]

- In both rural and urban areas, the cost of children for parents is increased by the introduction of compulsory education, as well as an increased need to educate children so they can take up respected positions in society. Children are increasingly prohibited by law from working outside the household; they make an increasingly limited contribution to the household, as schoolchildren are increasingly exempted from expectations of contributing significantly to domestic work. Even in equatorial Africa, children (under the age of 5) are now required to own clothes and shoes, and they may even need school uniforms. Parents begin to consider it a duty to buy children's books and toys. Partly due to education and access to family planning, people begin to reassess their need for children and their ability to raise them.[15]

- Increasing literacy and employment lower the uncritical acceptance of childbearing and motherhood as measures of a woman's status. Working women have less time to raise children; this situation is particularly problematic where fathers traditionally make little or no contribution to child-raising, such as in Southern Europe or Japan. Valuation of women beyond childbearing and motherhood becomes important.

- Improvements in contraceptive technology are now a major factor in fertility decline. Changes in values around children and gender are as important as the availability of contraceptives and knowledge of their use.

The resulting changes in the age structure of the population include a decline in the youth dependency ratio and eventually population aging. The population structure becomes less triangular and more like an elongated balloon. During the period between a decline in youth dependency and an increase in old-age dependency, there is a demographic window of opportunity; this can potentially produce economic growth through an increase in the ratio of working-age to dependent population—the demographic dividend.

However, unless factors such as those listed above are allowed to operate, a society's birth rates may not drop to a low level in due time; this situation implies that the society cannot proceed to Stage 3 and is locked in what is called a demographic trap.

Countries that have experienced a significant fertility decline from their pre-transition levels include the following:

- Decline of more than 50%: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Panama, Jamaica, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Lebanon, South Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, and many Pacific islands.

- Decline of 25–50%: Guatemala, Tajikistan, Egypt, and Zimbabwe.

- Decline of less than 25%: Sudan, Niger, Afghanistan.

Stage 4

[edit]

Stage 4 occurs when birth and death rates are both low, leading to total population stability. Death rates are low for a number of reasons, primarily lower rates of disease and increased food production. The birth rate is low because people have more opportunities to decide whether they want children. This situation is made possible by improvements in contraception, or by women gaining more independence and work opportunities.[21] The Demographic Transition Model is only a suggestion about the future population levels of a country, rather than a prediction.

Countries that were at this stage—with a total fertility rate between 2.0 and 2.5—in 2015 include the following: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cabo Verde, El Salvador, Faroe Islands, Grenada, Guam, India, Indonesia, Kosovo, Libya, Malaysia, Maldives, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, New Caledonia, Nicaragua, Palau, Peru, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Tunisia, Turkey, and Venezuela.[22]

Stage 5

[edit]

The original Demographic Transition Model includes only four stages, but additional stages have been proposed. Both more-fertile and less-fertile futures have been proposed for Stage 5.

Some countries have sub-replacement fertility, i.e., below 2.1–2.2 children per woman. Replacement fertility is generally slightly higher than 2—the level which replaces the two parents, achieving equilibrium—because boys are born more often than girls (about 1.05–1.1 to 1), and to compensate for deaths before full reproduction. Many European and East Asian countries now have higher death rates than birth rates. Population aging and population decline may eventually occur, assuming that the fertility rate remains constant and sustained mass immigration does not occur.

Using data through 2005, researchers have suggested that the negative relationship between development—as measured by the Human Development Index (HDI)—and birth rates had reversed at very high levels of development. In many countries with very high levels of development, fertility rates were approaching two children per woman in the early 2000s.[3][23] However, fertility rates declined significantly between 2010 and 2018 in many countries with very high development, including in countries with high levels of gender parity. The global data no longer support the suggestion that fertility rates tend to broadly rise at very high levels of national development.[24]

From the point of view of evolutionary biology, wealthier people having fewer children is unexpected, since natural selection would be expected to favor individuals who are willing and able to convert plentiful resources into plentiful fertile descendants. This apparent paradox may be the result of a departure from the environment of evolutionary adaptedness.[13][25][26]

Most models posit that the birth rate will stabilize at a low level indefinitely. Some dissenting scholars note that the modern environment is exerting evolutionary pressure toward higher fertility, and that due to individual natural selection or cultural selection, birth rates may eventually rise again. Part of the "cultural selection" hypothesis is that the variance in birth rate between cultures is significant; for example, some religious cultures have a higher birth rate that is not accounted for by differences in income.[27][28][29] In his book Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?, the demographer Eric Kaufmann argues that demographic trends point to religious fundamentalists greatly increasing as a share of the population over the next century.[30][31]

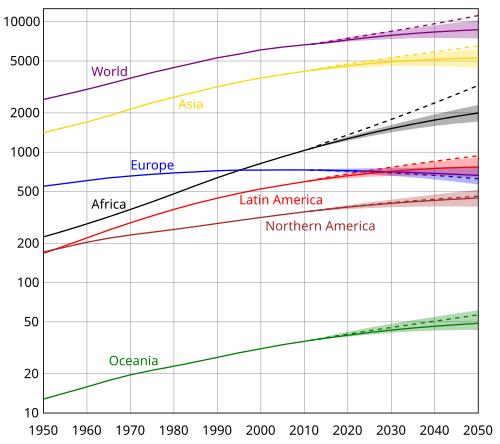

The scholar Jane Falkingham of Southampton University has noted that "We've actually got population projections wrong consistently over the last 50 years... we've underestimated the improvements in mortality... but also we've not been very good at spotting the trends in fertility."[13] In 2004, a United Nations office published its estimates for global population in the year 2300; estimates ranged from a "low estimate" of 2.3 billion (tending toward -0.32% per year) to a "high estimate" of 36.4 billion (tending toward +0.54% per year). These estimates were contrasted with a deliberately "unrealistic", illustrative "constant fertility" scenario of 134 trillion (which will pertain if 1995–2000 fertility rates remain constant into the distant future).[13][32]

Effects on age structure

[edit]

The decline in death rate and birth rate that occurs during the demographic transition may transform the age structure of a society. When the death rate declines during the second stage of the transition, the result is primarily an increase in the younger population. This occurs because when the death rate is high (Stage 1), the infant mortality rate is very high, often more than 200 deaths per 1000 children born. As the death rate falls, this decline may lead to a lower infant mortality rate and increased child survival.

Over time, as individuals with increased survival rates age, there may also be an increase in the number of older children, teenagers, and young adults. This trend implies that there is an increase in the fertile population proportion; with constant fertility rates, this may lead to an increase in the number of children born. This development will further increase the growth of the child population. The second stage of the demographic transition, therefore, implies a rise in child dependency and creates a youth bulge in the population structure.[33]

As a population continues to move through the demographic transition into the third stage, fertility declines, and the youth bulge prior to the decline ages out of child dependency into working age. This stage of the transition is often referred to as the golden age, and it is typically when populations experience the greatest advancements in living standards and economic development.[33] However, further declines in both mortality and fertility will eventually result in an aging population, as well as a rise in the age dependency ratio. An increase in the age dependency ratio often indicates that a population has reached below-replacement levels of fertility; as a result, it does not have enough people of working age to support the economy and the growing dependent population.[33]

Historical studies

[edit]

Europe

[edit]Britain

[edit]Between 1750 and 1975, England experienced the transition from high to low levels of both mortality and fertility. A major factor was the sharp decline in the death rate due to infectious diseases, which has fallen from about 11 per 1,000 to less than 1 per 1,000.[34] By contrast, the death rate from other causes was 12 per 1,000 in 1850, and it has not declined markedly.[citation needed] In general, scientific discoveries and medical breakthroughs did not contribute significantly to the early major decline in mortality from infectious diseases.[citation needed]

Ireland

[edit]In the 1980s and early 1990s, Ireland's demographic status converged to the European norm. Mortality rose above the European Community's average, and in 1991, Irish fertility fell to replacement level. The peculiarities of Ireland's past demography and its recent rapid changes challenge established theory. These recent changes have mirrored internal changes in Irish society with respect to several factors: family planning, women in the workforce, the sharply declining power of the Catholic Church, and the emigration factor.[35]

France

[edit]France displays significant divergences from the standard model of Western demographic evolution. The uniqueness of the French case arises from its specific demographic history, historical cultural values, and internal regional dynamics. France's demographic transition was unusual in that mortality and natality decreased at the same time; thus, there was no demographic boom during the 19th century.[36]

France's demographic profile is similar to those of its European neighbors and developed countries in general, yet it seems to be staving off the population decline typical of Western countries. With 62.9 million inhabitants in 2006, France was the second most populous country in the European Union; it displayed a certain demographic dynamism, with a growth rate of 2.4% between 2000 and 2005, above the European average. More than two-thirds of that growth can be ascribed to a natural increase resulting from high fertility and birth rates. In contrast, France is a developed nation whose migratory balance is rather weak, which is a unique feature at the European level. Several interrelated reasons account for these singularities, particularly the impact of pro-family policies, along with more unmarried households and out-of-wedlock births. These general demographic trends parallel equally important changes in regional demographics.

Since 1982, the same significant tendencies have occurred throughout mainland France:

- demographic stagnation in the least-populated rural regions and industrial regions in the northeast

- strong growth in the southwest and along the Atlantic coast

- dynamism in metropolitan areas

Shifts in population between regions account for most of the differences in growth. The varying demographic evolution of regions can be analyzed through the filter of several parameters—including residential facilities, economic growth, and urban dynamism—which yield several distinct regional profiles. The distribution of the French population therefore seems increasingly defined by two factors: interregional mobility and the residential preferences of individual households.

These challenges, linked to configurations of population and the dynamics of distribution, inevitably raise the issue of town and country planning. The most recent census figures show an outpouring of the urban population, which implies that fewer rural areas continue to register a negative migratory flow—two-thirds of rural communities have shown some since 2000. The spatial demographic expansion of large cities amplifies the process of peri-urbanization, yet it is also accompanied by selective residential movement, social selection, and sociospatial segregation based on income.[37]

Asia

[edit]In 2006, Geoffrey McNicoll examined common features behind the striking changes in health and fertility in East and Southeast Asia during the 1960s–1990s. He focused on seven countries:

- Taiwan and South Korea ("tiger" economies)

- Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia ("second wave" countries)

- China and Vietnam ("market-Leninist" economies)

Demographic change can be seen as a by-product of social and economic development, accompanied by strong government pressure in some cases. An effective, often authoritarian, local administrative system could provide a framework for promotion and services in health, education, and family planning. Economic liberalization increased economic opportunities and risks for individuals, while also increasing the price and often reducing the quality of these services—all of which affected demographic trends.[38]

India

[edit]In 2013, Goli and Arokiasamy indicated that India has had a sustainable demographic transition beginning in the mid-1960s and a fertility transition beginning after 1965.[39] As of 2013, India is in the latter half of the third stage of the demographic transition, with a population of 1.23 billion.[40] The country is nearly 40 years behind in the demographic transition process relative to developed countries such as the member states of the EU and Japan. The present demographic transition stage of India, together with its higher population base, will yield a rich demographic dividend in future decades.[41]

Korea

[edit]In 2007, Soo Cha Myung analyzed a panel data set to explore how industrial revolution, demographic transition, and human capital accumulation interacted in Korea from 1916 to 1938. Income growth and public investment in health caused mortality to fall, which suppressed fertility and promoted education. Several factors—industrialization, a skill premium, and a closing gender wage gap—further induced parents to opt for child quality. Expanding demand for education was accommodated by an active program for building public schools. The interwar agricultural depression aggravated traditional income inequality, raising fertility and impeding the spread of mass schooling. Landlordism collapsed in the wake of decolonization, and the consequent reduction in inequality accelerated human and physical capital accumulation, leading to growth in South Korea.[42]

China

[edit]China experienced a demographic transition, with a high death rate and a low fertility rate from 1959 to 1961, because of the Great Chinese Famine.[4] However, as a result of the economic improvement, the birth rate increased and the mortality rate declined in China before the early 1970s.[7] In the 1970s, China's birth rate fell at an unprecedented rate, which had not been experienced by any other population in a comparable time span. The birth rate fell from 6.6 births per woman before 1970 to 2.2 births per woman in 1980. This rapid fertility decline was caused by government policy: in particular, the "later, longer, fewer" policy of the early 1970s and the one-child policy of the late 1970s significantly influenced the Chinese demographic transition.[43] As the demographic dividend gradually disappeared, the government abandoned the one-child policy in 2011 and fully ended the two-child policy as of 2015. The two-child policy has had some positive effects on fertility, which continuously increased until 2018. However, fertility started to decline after 2018; meanwhile, there has been no significant change in mortality during the past 30 years.

Madagascar

[edit]Campbell has studied the demography of 19th-century Madagascar in the light of demographic transition theory. Both supporters and critics of the theory maintain an intrinsic opposition between human and "natural" factors—such as climate, famine, and disease—influencing demography. These people also assume a sharp chronological divide between the precolonial and colonial eras; they argue that whereas "natural" demographic influences were of greater importance in the former period, human factors predominated thereafter. Campbell maintains that in 19th-century Madagascar, the human factor, in the form of the Merina state, was the predominant demographic influence. However, the impact of the state was felt through natural forces, and this impact varied over time. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Merina policies stimulated agricultural production; this helped to create a larger and healthier population, and it laid the foundation for Merina military and economic expansion within Madagascar.

From 1820 onward, the cost of this expansionism led the state to increase its exploitation of forced labor at the expense of agricultural production, thereby transforming it into a negative demographic force. Infertility and infant mortality— which were probably more significant influences on overall population levels than the adult mortality rate—increased from 1820 onward due to disease, malnutrition, and stress, all of which stemmed from the state's forced labor policies. Available estimates indicate little (if any) population growth for Madagascar between 1820 and 1895. The demographic "crisis" in Africa is ascribed by critics of demographic transition theory to the colonial era; in Madagascar, this crisis stemmed from the policies of the imperial Merina regime, which in this sense formed a link to the French regime of the colonial era. Campbell thus questioned the underlying assumptions governing the debate about historical demography in Africa; he suggested that the demographic impact of political forces be reevaluated in terms of their changing interaction with "natural" demographic influences.[44]

Russia

[edit]Russia entered Stage 2 of the transition during the 18th century, simultaneously with the rest of Europe, though the effect of the transition remained limited to a modest decline in death rates and steady population growth. The population of Russia nearly quadrupled during the 19th century, from 30 million to 133 million, and it continued to grow until the First World War and the turmoil that followed.[45] Russia then quickly transitioned through Stage 3 of the model. Though fertility rates rebounded initially and almost reached 7 children per woman during the mid-1920s, these rates were depressed by the 1931–1933 famine; they crashed because of the Second World War in 1941; and they only rebounded to a sustained level of 3 children per woman after the war. By 1970, Russia was firmly in Stage 4, with crude birth rates and crude death rates on the order of 15/1000 and 9/1000, respectively. Oddly, however, the birth rate entered a state of constant flux, repeatedly rising above 20/1000 or falling below 12/1000.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Russia underwent a unique demographic transition—observers call it a "demographic catastrophe": the number of deaths exceeded the number of births; life expectancy fell sharply (especially for men); and the number of suicides increased.[46] From 1992 through 2011, the number of deaths exceeded the number of births; from 2011 onward, the opposite has been the case.

United States

[edit]In 2002, Greenwood and Seshadri showed that from 1800 to 1940, a demographic shift occurred: from a primarily rural US population with high fertility, with an average of seven children born per white woman, to a minority (43%) rural population with low fertility, with an average of two children born per white woman. This shift resulted from technological progress. A sixfold increase in real wages made children more expensive in terms of lost opportunities for work; increases in agricultural productivity reduced the rural demand for labor, a substantial portion of which had traditionally been performed by children in farm families.[47]

A simplification of DTM theory proposes an initial decline in mortality, followed by a later drop in fertility. The changing demographics of the US during the last two centuries did not parallel this model. Beginning around 1800, fertility declined sharply; at that time, the average woman usually had seven births per lifetime, but by 1900, this number had dropped to just above four. This mortality decline was not observed in the US until almost 1900, a hundred years after the drop in fertility.

However, this late decline started from a very low initial level. During the 17th and 18th centuries, crude death rates in much of colonial North America ranged from 15 to 25 deaths per 1000 residents per year.[48][49] (Levels of up to 40 deaths per 1000 residents are typical during Stages 1 and 2.) Life expectancy at birth was approximately 40 years; in some places, it reached 50. A resident of 18th-century Philadelphia who reached the age of 20 could expect to live for another 40 years, on average.

This phenomenon is explained by the colonization pattern in the United States. The country's sparsely populated interior had ample room to accommodate all the "excess" people, counteracting mechanisms—the spread of communicable diseases due to overcrowding, low real wages, and insufficient calories per capita because of limited available agricultural land—which led to high mortality in the Old World. With low mortality but birth rates typical of Stage 1, the United States necessarily experienced exponential population growth—from fewer than 4 million people in 1790, to 23 million in 1850, to 76 million in 1900.

The only region where this pattern did not fit was the American South. The prevalence of deadly endemic diseases, such as malaria, kept mortality as high as 45–50 per 1000 residents per year in 18th-century North Carolina. In New Orleans, mortality remained so high (mainly because of yellow fever) that the city was characterized as the "death capital of the United States"—at the level of 50 per 1000 residents or higher—well into the second half of the 19th century.[50]

Today, the US is recognized as having both low fertility rates and low mortality rates. Specifically, the birth rate is 14 per 1000 people per year, and the death rate is 8 per 1000 people per year.[51]

Critical evaluation

[edit]Because the DTM is only a model, it cannot predict the future, but it does suggest an underdeveloped country's future birth and death rates, along with total population size. In particular, the DTM does not comment on changes in population due to migration. Moreover, the model does not necessarily apply at very high levels of development.[3][24]

The DTM does not account for recent phenomena such as AIDS; in these areas, HIV has become the leading cause of mortality. Some trends in infant mortality from waterborne bacteria are also disturbing. In countries such as Malawi, Sudan, and Nigeria, for example, progress in the DTM clearly stopped and reversed between 1975 and 2005.[52]

The DTM assumes that population changes are induced by industrial change and increased wealth, without taking into account the role of social change—e.g., the education of women—in determining birth rates. In recent decades, more work has been done on developing the social mechanisms behind the transition.[53]

The DTM assumes that the birth rate is independent of the death rate. Nevertheless, demographers maintain that there is no historical evidence for society-wide fertility rates rising significantly after high-mortality events. Notably, some historic populations have taken many years to replace lives after events such as the Black Death.

Some people have claimed that the DTM does not explain the early fertility declines in much of Asia during the second half of the 20th century, nor the delays in fertility decline in parts of the Middle East. Nevertheless, the demographer John C. Caldwell has suggested that the reason for the rapid fertility decline in some developing countries—compared to Western Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—is mainly due to government programs, as well as a massive investment in education both by governments and parents.[17]

The DTM does not effectively explain the impact of government policies on birth rate. In some developing countries, governments often implement policies to control an increase in fertility rates. China, for example, underwent a fertility transition in 1970, and the Chinese experience was largely influenced by government policy. In particular, two policies—the "later, longer, fewer" policy of 1970 and the one-child policy enacted in 1979— encouraged people to have fewer children in later life. The fertility transition indeed stimulated economic growth and influenced the demographic transition in China.[54]

Second demographic transition

[edit]The second demographic transition (SDT) is a conceptual framework first formulated in 1986 by Ron Lesthaeghe and Dirk van de Kaa.[55]: 181 [55][56][57] SDT addressed the changes in the patterns of sexual and reproductive behavior that occurred in North America and Western Europe from about 1963—when the birth control pill and other cheap, effective contraceptive methods such as the intrauterine device (IUD) were adopted by the general population—to the present. Combined with the sexual revolution, as well as the increased role of women in society and the workforce, the resulting changes have profoundly affected the demographics of industrialized countries; this has resulted in a sub-replacement fertility level.[58]

The changes mentioned above include the following:

- increased numbers of women choosing not to marry or have children

- increased cohabitation outside marriage

- increased childbearing by single mothers

- increased participation by women in higher education and professional careers

- other changes

These changes are associated with increased individualism and autonomy, particularly for women. Traditional and economic motivations have changed to self-realization instead.[59]

In 2015, Nicholas Eberstadt, a political economist at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, described the second demographic transition as one in which "long, stable marriages are out, and divorce or separation are in, along with serial cohabitation and increasingly contingent liaisons."[60] The scholar S. Philip Morgan thought that the current development orientation for SDT is problematic. Social demographers should explore a theory that is not based on stages, and that does not establish a single, linear development path toward a final stage—in the case of SDT, a hypothesis that looks like the advanced Western countries that most embrace postmodern values.

However, SDT theory has not proposed a single line or teleological evolution based on phases, as was the case for theories of the First Demographic Transition (FDT). As is evident in Lesthaeghe's empirical studies, major attention is being paid instead to several dimensions:

- historical path dependency

- heterogeneity in the SDT patterns of development

- forms of family and lineage organization

- economic and especially ideational developments[61]

For instance, the European pattern—with almost simultaneous manifestation of all SDT demographic characteristics—is not being replicated elsewhere. The Latin American countries experienced major growth in premarital cohabitation, in which the upper classes were catching up with pre-existing higher levels among less educated people and certain ethnic groups.[62] To date, however, the other major SDT indicator—namely, fertility postponement—is largely absent.

The opposite holds for Asian patriarchal societies, which have traditionally strong rules for arranged endogamous marriage and male dominance. In industrialized East Asian societies, a major postponement occurred in union formation and parenthood; this led to increased numbers of single people and low, sub-replacement levels of fertility. In such historically patriarchal societies, a free choice of partner is to be avoided; hence, there is a strong stigma against premarital cohabitation. However, after the turn of the century, cohabitation did develop in Japan, China, Taiwan, and the Philippines.[63] The proportions are still moderate, and pregnancies in cohabiting unions are typically followed by forced marriages or abortions. Parenthood among cohabitants is still rare.[64] Finally, Hindu and Muslim countries could reach replacement level fertility, but no significant fertility postponement or increase in premarital cohabitation has occurred. Hence, these countries are completing the FDT, and they are not in any sort of initiation phase for the SDT.

Sub-Saharan African populations exhibit yet another sui generis pattern. These societies have exogamous union formation and weaker marriage institutions. Under these conditions, cohabitation seems to grow among both poorer and wealthier population segments. Among the poorer segment, cohabitation reflects the "pattern of disadvantage"; among the wealthier segment, cohabitation is a means of avoiding an inflated bride price. However, Sub-Saharan African populations have not yet completed the FDT fertility transition, and several West African populations have barely started it. Hence, there is a striking disconnection between trends in fertility and partnership formation.

In conclusion, the development of the SDT is characterized by as much pattern heterogeneity as was the historical FDT.[65]

See also

[edit]- Birth dearth

- Demographic dividend

- Demographic economics

- Demographic trap

- Demographic window

- Epidemiological transition

- Mathematical model of self-limiting growth

- Neolithic demographic transition

- Migration transition model

- Population change

- Population pyramid

- Rate of natural increase

- Self-limiting growth in biological population at carrying capacity

- Transition economy

- Waithood

- World population milestones

- r/K life history theory

- Russian cross

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Models of Demographic Transition [ Biz/ed Virtual Developing Country ]". web.csulb.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded (2011). Unified Growth Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3886-8.

- ^ a b c d Myrskylä, Mikko; Kohler, Hans-Peter; Billari, Francesco C. (2009). "Advances in development reverse fertility declines". Nature. 460 (7256): 741–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..741M. doi:10.1038/nature08230. PMID 19661915. S2CID 4381880.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded (17 February 2011). "The demographic transition: causes and consequences". Cliometrica. 6 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1007/s11698-011-0062-7. PMC 4116081. PMID 25089157.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded (2005). "The Demographic Transition and the Emergence of Sustained Economic Growth" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 3 (2–3): 494–504. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.494. hdl:10419/80187.

- ^ "Warren Thompson". Encyclopedia of Population. Vol. 2. Macmillan Reference. 2003. pp. 939–40. ISBN 978-0-02-865677-9.

- ^ a b Landry, Adolphe (December 1987). "Adolphe Landry on the Demographic transition Revolution". Population and Development Review. 13 (4): 731–740. doi:10.2307/1973031. JSTOR 1973031.

- ^ Woods, Robert (2000-10-05). The Demography of Victorian England and Wales. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-521-78254-8.

- ^ Vobecka, Jana (2013). Demographic Avant-Garde: Jews in Bohemia between the Enlightenment and the Shoah. Central European University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-615-5225-33-8.

- ^ John C, Caldwell (1976). "Toward A Restatement of Demographic Transition Theory". Population and Development Review. 2 (3): 321–366. doi:10.2307/1971615. JSTOR 1971615.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Montgomery, Keith. "Demographic Transition". WayBackMachine. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019.

- ^ "Demographic transition", Geography, About, archived from the original on 2017-02-26, retrieved 2010-10-26.

- ^ a b c d Can we be sure the world's population will stop rising?, BBC News, 13 October 2012

- ^ "Demographic Transition Model". geographyfieldwork.com.

- ^ a b Caldwell (2006), Chapter 5

- ^ "BBC bitesize". Archived from the original on October 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Caldwell (2006), Chapter 10

- ^ "Stage 3 of the Demographic Transition Model - Population Education". 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Demographic transition", Geography, Marathon, UWC, archived from the original on 2019-06-05, retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "Third Cousins Have Greatest Number Of Offspring, Data From Iceland Shows", ScienceDaily, 8 February 2008, archived from the original on 2 January 2021.

- ^ "Demographic", Main vision.

- ^ "Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ "The best of all possible worlds?", The Economist, 6 August 2009.

- ^ a b Gaddy, Hampton Gray (2021-01-20). "A decade of TFR declines suggests no relationship between development and sub-replacement fertility rebounds". Demographic Research. 44 5: 125–142. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2021.44.5. ISSN 1435-9871.

- ^ Clarke, Alice L.; Low, Bobbi S. (2001). "Testing evolutionary hypotheses with demographic data" (PDF). Population and Development Review. 27 (4): 633–660. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00633.x. hdl:2027.42/74296.

- ^ Daly, Martin; Wilson, Margo I (26 June 1998). "Human evolutionary psychology and animal behaviour" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 57 (3). Department of Psychology, McMaster University: 509–519. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.1027. PMID 10196040. S2CID 4007382. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Kolk, M.; Cownden, D.; Enquist, M. (29 January 2014). "Correlations in fertility across generations: can low fertility persist?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1779) 20132561. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2561. PMC 3924067. PMID 24478294.

- ^ Burger, Oskar; DeLong, John P. (28 March 2016). "What if fertility decline is not permanent? The need for an evolutionarily informed approach to understanding low fertility". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1692) 20150157. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0157. PMC 4822437. PMID 27022084.

- ^ "Population paradox: Europe's time bomb". The Independent. 9 August 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ "Shall the religious inherit the earth?". Mercator Net. April 6, 2010. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ McClendon, David (Autumn 2013). "Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? Demography and Politics in the Twenty-First Century, by ERIC KAUFMANN". Sociology of Religion. 74 (3): 417–9. doi:10.1093/socrel/srt026.

- ^ "World Population to 2300" (PDF). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Weeks, John R. (2014). Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues. Cengage Learning. pp. 94–97. ISBN 978-1-305-09450-5.

- ^ Harris, Bernard. "Health by Association". International Journal of Epidemiology: 488–490.

- ^ Coleman, DA (1992), "The Demographic Transition in Ireland in International Context", Proceedings of the British Academy (79): 53–77.

- ^ Vallin, Jacques; Caselli, Graziella (May 1999). "Quand l'Angleterre rattrapait la France". Population & Sociétés (in French) (346).

- ^ Baudelle, Guy; Olivier, David (2006), "Changement Global, Mondialisation et Modèle De Transition Démographique: réflexion sur une exception française parmi les pays développés", Historiens et Géographes (in French), 98 (395): 177–204, ISSN 0046-757X

- ^ McNicoll, Geoffrey (2006). Policy Lessons of the East Asian Demographic Transition (Report). Policy Research Division Working Paper. New York: Population Council. doi:10.31899/pgy2.1041.

- ^ Goli, Srinivas; Arokiasamy, Perianayagam (2013-10-18). Schooling, C. Mary (ed.). "Demographic Transition in India: An Evolutionary Interpretation of Population and Health Trends Using 'Change-Point Analysis'". PLOS ONE. 8 (10) e76404. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876404G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076404. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3799745. PMID 24204621.

- ^ "The arithmetic's of Indian population". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "India vs China vs USA vs World". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Myung, Soo Cha (July 2007), Industrial Revolution, Demographic Transition, and Human Capital Accumulation in Korea, 1916–38 (PDF) (working Paper), KR: Naksungdae Institute of Economic Research.

- ^ John, Bongaarts; Susan, Greenhalgh (1985). "An alternative to the One-Child Policy in China". Population and Development Review. 11 (4): 585–617. doi:10.2307/1973456. JSTOR 1973456.

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (1991), "State and Pre-colonial Demographic History: the Case of Nineteenth-century Madagascar", Journal of African History, 32 (3): 415–45, doi:10.1017/s0021853700031534, ISSN 0021-8537.

- ^ "Population of Eastern Europe". tacitus.nu. Archived from the original on 2018-01-08. Retrieved 2015-09-30.

- ^ Demko, George J, ed. (1999), Population under Duress: The Geodemography of Post-Soviet Russia, et al, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-8939-9[page needed]

- ^ Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth (January 2002). The U.S. Demographic Transition (Report). NBER Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research. SSRN 297952.

- ^ Herbert S. Klein. A Population History of the United States. p. 39.

- ^ Michael R. Haines; Richard H. Steckel. A Population History of North America. pp. 163–164.

- ^ Haines, Michael R. (July 2001). "The Urban Mortality Transition in the United States, 1800–1940". NBER Historical Working Paper No. 134. doi:10.3386/h0134.

- ^ "US", World Factbook, USA: CIA, 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Nigeria: Reversal of Demographic Transition", Population action, November 2006, archived from the original on 2007-04-11, retrieved 2007-02-09.

- ^ Caldwell, John C.; Bruce K Caldwell; Pat Caldwell; Peter F McDonald; Thomas Schindlmayr (2006). Demographic Transition Theory. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-4020-4373-4.

- ^ Carl-johan, dalgaard; pablo, selaya (2015). "Climate and the Emergence of Global Income". The Review of Economic Studies. 83 (4): 1334–1363. JSTOR 26160242.

- ^ a b Ron J. Lesthaeghe (2011), "The "second demographic transition": a conceptual map for the understanding of late modern demographic developments in fertility and family formation", Historical Social Research, 36 (2): 179–218

- ^ Ron Lesthaeghe; Dirk van de Kaa (1986). "Twee demografische transities? [Second Demographic Transition]". Bevolking: groei en krimp [Population: growth and shrinkage]. Deventer : Van Loghum Slaterus. pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-90-368-0018-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)(in Dutch with summaries in English) - ^ Ron J. Lesthaeghe (1991), The Second Demographic Transition in Western countries: An interpretation (PDF), IPD Working Paper, Interuniversity Programme in Demography, retrieved February 26, 2017

- ^ van de Kaa, Dirk J. (29 January 2002). "The Idea of a Second Demographic Transition in Industrialized Countries" (PDF). The Japanese Journal of Population. 1 (1): 1–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Ron Lesthaeghe (December 23, 2014). "The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (51): 18112–18115. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11118112L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420441111. PMC 4280616. PMID 25453112.

- ^ Nicholas Eberstadt (February 21, 2015), The Global Flight From the Family: It's not only in the West or prosperous nations—the decline in marriage and drop in birth rates is rampant, with potentially dire fallout, Wall Street Journal, retrieved February 26, 2017,

'They're getting divorced, and they'll do anything NOT to get custody of the kids." So reads the promotional poster, in French, for a new movie, "Papa ou Maman"

- ^ Johan Surkyn and Ron Lesthaeghe, 2004: Value Orientations and the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe- An Update. Demographic Research, Special collection, 3: 45-86. Ron Lesthaeghe, 2010: The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review, 36 (2), 211-251

- ^ Albert Esteve and Ron Lesthaeghe (eds), 2016. Cohabitation and Marriage in the Americas - Geo-historical Legacies and New Trends. Springer Open, Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland, 291p.

- ^ James Raymo, M. Iwasawa and Larry Bumpass, 2009: Cohabitation and Family Formation in Japan, Demography 46 (4), 758-803. Jia Yu and Yu Xie, 2015:Cohabitation in China: Trends and Determinants. Population and Development Review, 41 (4), 607-628.

- ^ Ron Lesthaeghe, 2020a: The Second Demographic Transition: Cohabitation, Kim Halford and Fons van de Vijver (eds): Cross-Cultural Family Research and Practice. Academic Press/ Elsevier, 103-144.

- ^ Ron Lesthaeghe, 2020b: The Second Demographic Transition 1986-2020, Sub-Replacement Fertility and Rising Cohabitation - A Global Update. Genus 76(1)

References

[edit]- Carrying capacity

- Caldwell, John C. (1976). "Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory". Population and Development Review. 2 (3/4): 321–66. doi:10.2307/1971615. JSTOR 1971615.

- ————————; Bruce K Caldwell; Pat Caldwell; Peter F McDonald; Thomas Schindlmayr (2006). Demographic Transition Theory. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-4020-4373-4.

- Chesnais, Jean-Claude. The Demographic Transition: Stages, Patterns, and Economic Implications: A Longitudinal Study of Sixty-Seven Countries Covering the Period 1720–1984. Oxford U. Press, 1993. 633 pp.

- Coale, Ansley J. 1973. "The demographic transition," IUSSP Liege International Population Conference. Liege: IUSSP. Volume 1: 53–72.

- ————————; Anderson, Barbara A; Härm, Erna (1979). Human Fertility in Russia since the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press..

- Coale, Ansley J; Watkins, Susan C, eds. (1987). The Decline of Fertility in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press..

- Davis, Kingsley (1945). "The World Demographic Transition". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 237 (237): 1–11. doi:10.1177/000271624523700102. JSTOR 1025490. S2CID 145140681.. Classic article that introduced concept of transition.

- Davis, Kingsley. 1963. "The theory of change and response in modern demographic history." Population Index 29(October): 345–66.

- Kunisch, Sven; Boehm, Stephan A.; Boppel, Michael (eds): From Grey to Silver: Managing the Demographic Change Successfully, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-15593-2

- Friedlander, Dov; S Okun, Barbara; Segal, Sharon (1999). "The Demographic Transition Then and Now: Processes, Perspectives, and Analyses". Journal of Family History. 24 (4): 493–533. doi:10.1177/036319909902400406. ISSN 0363-1990. PMID 11623954. S2CID 36680992., full text in Ebsco.

- Galor, Oded (2005). "The Demographic Transition and the Emergence of Sustained Economic Growth" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 3 (2–3): 494–504. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.494. hdl:10419/80187.

- ———————— (2008). "The Demographic Transition". New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.). Macmillan..

- Gillis, John R., Louise A. Tilly, and David Levine, eds. The European Experience of Declining Fertility, 1850–1970: The Quiet Revolution. 1992.

- Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth (2002). "The US Demographic Transition". American Economic Review. 92 (2): 153–59. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.13.6505. doi:10.1257/000282802320189168. JSTOR 3083393.

- Harbison, Sarah F.; Robinson, Warren C. (2002). "Policy Implications of the Next World Demographic Transition". Studies in Family Planning. 33 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00037.x. JSTOR 2696331. PMID 11974418.

- Hirschman, Charles (1994). "Why fertility changes". Annual Review of Sociology. 20: 203–233. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.20.080194.001223. PMID 12318868.

- Jones, GW, ed. (1997). The Continuing Demographic Transition. et al.[ISBN missing]

- Korotayev, Andrey; Malkov, Artemy; Khaltourina, Daria (2006). Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow, Russia: URSS. p. 128. ISBN 978-5-484-00414-0.

- Kirk, Dudley (1996). "The Demographic Transition". Population Studies. 50 (3): 361–87. doi:10.1080/0032472031000149536. JSTOR 2174639. PMID 11618374.

- Borgerhoff, Luttbeg B; Borgerhoff Mulder, M; Mangel, MS (2000). "To marry or not to marry? A dynamic model of marriage behavior and demographic transition". In Cronk, L; Chagnon, NA; Irons, W (eds.). Human behavior and adaptation: An anthropological perspective. New York: Aldine Transaction. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-202-02044-0.

- Landry, Adolphe, 1982 [1934], La révolution démographique – Études et essais sur les problèmes de la population, Paris, INED-Presses Universitaires de France

- McNicoll, Geoffrey (2006). "Policy Lessons of the East Asian Demographic Transition". Population and Development Review. 32 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00103.x. JSTOR 20058849.

- Mercer, Alexander (2014), Infections, Chronic Disease, and the Epidemiological Transition. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press/Rochester Studies in Medical History, ISBN 978-1-58046-508-3

- Montgomery, Keith. "The Demographic Transition". Geography. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2014-04-25..

- Notestein, Frank W. 1945. "Population — The Long View," in Theodore W. Schultz, Ed., Food for the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Saito, Oasamu (1996). "Historical Demography: Achievements and Prospects". Population Studies. 50 (3): 537–53. doi:10.1080/0032472031000149606. ISSN 0032-4728. JSTOR 2174646. PMID 11618380..

- Soares, Rodrigo R., and Bruno L. S. Falcão. "The Demographic Transition and the Sexual Division of Labor," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 116, No. 6 (Dec., 2008), pp. 1058–104

- Szreter, Simon (1993). "The Idea of Demographic Transition and the Study of Fertility: A Critical Intellectual History". Population and Development Review. 19 (4): 659–701. doi:10.2307/2938410. JSTOR 2938410..

- ————————; Nye, Robert A; van Poppel, Frans (2003). "Fertility and Contraception During the Demographic Transition: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 34 (2): 141–54. doi:10.1162/002219503322649453. ISSN 0022-1953. S2CID 54023512., full text in Project Muse and Ebsco

- Thompson, Warren S (1929). "Population". American Journal of Sociology. 34 (6): 959–75. doi:10.1086/214874. S2CID 222441259.

After the next World War, we will see Germany lose more women and children and soon start again from a developing stage

. - World Bank, Fertility Rate