Pauline interpolations and forgeries

| Pauline interpolations and forgeries | |

|---|---|

| Overview of suspected textual insertions in authentic Pauline letters and of later pseudepigrapha attributed to Paul | |

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Author | Various authors claiming to be Paul |

| Language | Koine Greek, Coptic, later Latin and other versions |

| Period | 1st to 4th centuries CE |

| Books | Multiple letters and texts |

| Full text | |

Pauline interpolations and forgeries are two related phenomena in the textual history of the apostle Paul's writings. First, a number of brief passages within letters widely regarded as authentically Pauline are suspected of being later insertions, usually called interpolations. Second, several canonical letters and a large set of noncanonical writings from the second to fourth centuries present themselves as Pauline but are judged by most modern scholars to be pseudonymous. Together these issues are central to the study of the Pauline epistles, their transmission, and their reception in early Christianity.[1][2][3]

Scholars widely agree that seven of Paul's letters are authentic while the Pastoral Epistles are widely assessed as pseudonymous and the authorship of Colossians, Ephesians, and 2 Thessalonians continues to be debated.[4][5][6] Evangelical and confessional scholars frequently defend Pauline authorship for the disputed letters by appealing to secretarial practice, shifting audiences, and early attestation.[7][8] Across Christian traditions the letters retain canonical authority because ecclesial reception, rather than a single authorship verdict, governs their use in liturgy and doctrine.[9]

Following American New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman, ancient Christian "forgery" is the literary act of "making a false authorial claim," which ancient writers judged to be "a form of lying."[10] In broader canonical perspective, Ehrman describes early Christian literature as containing "falsely attributed and forged writings," and he notes that "a fair critical consensus holds" several New Testament letters are not by Paul.[11]

History

[edit]The high frequency of suspected interpolations and pseudepigraphical writings associated with Paul's letters stems from their early circulation as a collected corpus and their foundational role as the first substantial Christian prose texts. In the second century, Paul's letters were gathered, given new titles, and republished, creating opportunities for editorial modifications during public reading and copying.[12][13][14][15] Paul's name carried significant authority in early church debates about religious law, Gentile inclusion, and ecclesiastical organization. This led Gnostic, Jewish-Christian, and proto-orthodox communities to write texts, or produce counter-texts, under Paul's name to support their theological positions.[16][17][18][19][20] The authentic Pauline letters contain stylistic variations due to his use of secretaries, collaboration with coauthors, and the creation of composite texts. These variations facilitated the addition of explanatory notes and textual rearrangements that were sometimes incorporated into later manuscripts.[21][22][23][24][25] While pseudonymous writings exist under other apostolic names, the early date, extensive size, and widespread distribution of Paul's letters made them particularly susceptible to imitation and expansion in early Christian literature.[26][27]

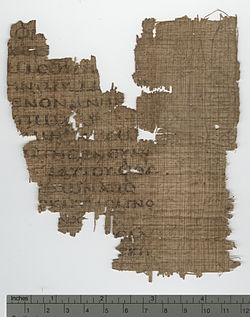

Early Christian communities wrote, collected, and circulated Paul's letters in groups. Studies of the Pauline epistles trace the development from single occasional letters to multi-letter collections that were copied and published in several forms before a more standard corpus emerged.[13][28] The papyrus P46 from around 200 CE preserves a large early collection that includes Romans, Hebrews, 1–2 Corinthians, Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians, and part of 1 Thessalonians, which shows that Hebrews could circulate inside a Pauline codex.[29][30]

Marcion's mid-second-century Apostolikon contained ten letters and labeled Ephesians as "to the Laodiceans," which confirms that titles and ordering varied across early collections.[18][31] The late second-century Muratorian fragment explicitly warns against letters "to the Laodiceans" and "to the Alexandrians" forged in Paul's name.[17]

Circa 198–203 CE,Tertullian says a presbyter in Asia composed the Acts of Paul out of love for Paul and was deposed when discovered.[32] The transmission of individual letters also shows editorial signs. Romans circulated with a movable doxology and shorter recensions, which indicate later handling of the text.[33][34] Scholars also note composite features in 2 Corinthians, where multiple letter-pieces may have been edited into a single work now preserved in the canon.[35]

Early canons of Paul

[edit]- c. 96 to 99 CE 1 Clement quotes or alludes to Romans, 1 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Titus, 1 Timothy, and Hebrews[36]

- c. 110 CE Ignatius of Antioch uses Romans, 1 Corinthians, Ephesians, Colossians, and 1 Thessalonians[37]

- c. 110 to 135 CE Polycarp cites 2 Thessalonians and echoes 1–2 Timothy among many other New Testament writings[38]

- c. 140 CE Marcion publishes a ten-letter Pauline collection that excludes the Pastorals and Hebrews[39]

- c. 140 to late 2nd century CE Muratorian fragment accepts the Pauline letters, warns against letters "to the Laodiceans" and "to the Alexandrians," and does not list Hebrews[40]

- c. 200 CE Papyrus 46 preserves a substantial Pauline codex that includes Hebrews within a Pauline sequence[41]

Evolution of modern Pauline criticism

[edit]

Nineteenth-century German theologian Ferdinand Christian Baur accepted only four Hauptbriefe (main letters) as authentic: Romans, 1-2 Corinthians, and Galatians.[42]

In the 1830s, Baur's Tübingen School read the remaining letters as second-century compositions that addressed conflict between Petrine and Pauline groups. He framed the discussion with a history of dogma approach.[43][44] By the 1860s, British and German scholars argued for a larger authentic core. J. B. Lightfoot defended authenticity on historical and philological grounds, and advances in textual criticism produced more stable Pauline editions for analysis.[45][46][47]

Adolf Deissmann argued in 1910 that Paul's writings are occasional letters addressed to specific audiences and situations. Work in papyrology and codicology, including publication of the early Pauline codex P46 from around 200 CE, encouraged study of collection and transmission alongside authorship.[12][48][41]

In 1913, Wilhelm Bousset examined lordship language and cultic titles, and in 1921 Rudolf Bultmann's form criticism focused on kerygma, rhetoric, and setting in life. That same year, P. N. Harrison analyzed vocabulary and style in the Pastoral epistles and argued for post-Pauline authorship, and conservative commentators presented counterarguments for Pauline authorship. In the 1950s and 60s, apocalyptic interpretations associated with Ernst Käsemann emphasized eschatology and divine agency in the undisputed letters.[49][50][51][52][53]

From the 1970s onward, rhetorical, intertextual, and social scientific methods broadened Pauline studies through targeted monographs and commentaries. Hans Dieter Betz's Hermeneia commentary on Galatians and Margaret M. Mitchell's study of reconciliation read the letters as crafted speeches whose argumentative stages can be outlined and, where seams appear, tested for partition or interpolation.[54][55] Richard B. Hays mapped Pauline use of scripture to trace discourse analytical echoes that clarify argumentative flow, while Stanley K. Stowers situated the epistles within Greco-Roman letter-writing conventions to explain shifts in voice.[56][57] Anthony Kenny supplemented those qualitative analyses with stylometric testing that quantified stylistic variance across the corpus.[58]

From 1963-2013, Krister Stendahl, E. P. Sanders, James D. G. Dunn, and N. T. Wright reframed Paul's language about law, justification, and Gentile inclusion. Their work encouraged readings of the undisputed letters within a Jewish context and supported models of a Pauline school to account for disputed letters.[59][60][61][62]

Harry Gamble (1995), David Trobisch (2000), and Benjamin Laird (2022) argued that second-century editors curated and published a Pauline collection, which helps explain how disputed letters and Hebrews circulated with undisputed works. Research on composition practices and secretarial assistance noted that dictation and coauthorship can shape style and vocabulary.[63][14][15][64]

In his seminal 2013 work, Forgery and Counterforgery, Bart D. Ehrman describes ancient Christian forgery as "the use of literary deceit," argues that forgery meant "making a false authorial claim," and concludes that in antiquity it was "a form of lying."[65]

Some introductions to New Testament studies, including Udo Schnelle, advise assessing "each Pauline letter separately" and judging possible insertions via a "case-by-case textual analysis" of "manuscript, context, and language." Similarly, proposed interpolations within authentic letters should be assessed one by one through careful analysis of manuscript evidence, contextual fit, and linguistic features.[5]

Methods used by scholars

[edit]Scholars combine internal, external, and contextual criteria when they evaluate possible interpolations or forgeries in writings attributed to Paul.[66][5]

| Category | Letters | Typical reasons adduced in scholarship |

|---|---|---|

| Undisputed core | Romans, 1–2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon | Strong early attestation, consistent Pauline style and theology, plausible historical setting [66][5] |

| Disputed | Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians | Vocabulary and style variation, different eschatology or ecclesiology, high literary dependence across letters. Many scholars defend authenticity and appeal to situation, audience, and use of a secretary [66][67][8] |

| Widely judged pseudonymous | 1–2 Timothy, Titus | Advanced church order and offices, distinctive vocabulary and style, difficulty fitting travels into known chronology [66][5] |

| Anonymous, sometimes bound with Paul in early codices | Hebrews | Modern consensus rejects Pauline authorship. Early collectors sometimes placed Hebrews with Pauline letters, which shows fluid collection practice [68][41] |

The addressee of Ephesians in 1:1 is uncertain in several early witnesses, where "in Ephesus" is absent. This omission has led many to view Ephesians as a circular letter, possibly the "letter from Laodicea" in Colossians 4:16, which illustrates how titles and destinations could shift in the process of collection and rereading.[69][70]

Internal and external evidence

[edit]Internal evidence concerns authorial claims, self-references, and coherence with the thought and style of other Pauline letters. External evidence concerns citations, allusions, and early canon lists that show a letter was in use. Both sets of evidence are weighed together because early transmission was fluid and later communities sometimes attributed anonymous or derivative works to Paul.[66][5]

Language, style, and theology

[edit]Vocabulary, syntax, and rhetorical features are compared across the corpus. Many scholars also track how theological themes such as law, eschatology, and church order are developed. Some disputed letters can be defended as Pauline by appeal to topic, audience, or editorial assistance. The Pastoral Epistles (1-2 Timothy, Titus) and some disputed letters like Ephesians and Colossians are explained by many scholars as post-Pauline compositions that reuse Pauline language and ideas.[67][8]

Historical setting and secretarial practice

[edit]Historical fit within Paul's travels and circumstances is considered with caution, since our narrative sources are limited. Scholars also note that Paul could dictate to or work through secretaries, which can account for stylistic and structural variation across letters.[21][71][72]

Interpolations

[edit]Scholars explain that interpolations cluster in the undisputed Pauline letters because those writings circulated earliest, were read publicly, and were edited together as a corpus, conditions that allowed marginal glosses and explanatory notes to be taken into the text during copying.[73][74][75] Textual critics point to concrete cases inside authentic letters, for example the secondary placement of 1 Corinthians 14:34–35 in Western witnesses and the movable doxology in Romans, which document early scribal handling and recensional activity.[76][77]

Modern scholarship widely recognizes seven letters as authentically Pauline, namely Romans, 1–2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon.[78]

Within these, several passages are proposed as later insertions.

1 Corinthians 14:34–35

[edit]"Let your women keep silence in the churches, for it is not permitted unto them to speak, but they are commanded to be under obedience, as also saith the law. And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home, for it is a shame for women to speak in the church."[79]

These verses appear to conflict with 1 Corinthians 11:5 where women pray and prophesy. A group of Western witnesses relocates the two verses to the chapter end. Bruce M. Metzger records a transposition after 14:40 in codices D, F, G and allied Latin witnesses, which he attributes to a scribe's attempt to fit the directive into the argument.[80] On internal grounds Gordon D. Fee argues these verses are a non-Pauline gloss that entered early.[81]

Scholars like Anthony C. Thiselton and Craig S. Keener defend authenticity and explain the text as a local regulation or as quoted Corinthian speech refuted by Paul.[82]

1 Thessalonians 2:14–16

[edit]"For you, brothers and sisters, became imitators of the churches of God in Judea in Christ Jesus. For you suffered from your own countrymen the same things they did from the Jews, who both killed the Lord Jesus and the prophets and drove us out, and they displease God and oppose all people, forbidding us to speak to the Gentiles that they might be saved, to fill up their sins always, for the wrath is come upon them to the uttermost."[79]

Because the passage appears to presuppose a completed divine wrath and because its tone differs from Romans 9–11, some scholars argue it is a later addition. Birger A. Pearson proposed a Deutero-Pauline interpolation.[83]

Markus Bockmuehl defends Pauline authorship as early rhetorical hyperbole in a context of persecution.[84]

2 Corinthians 6:14–7:1

[edit]

"Be not unequally yoked together with unbelievers. For what fellowship has righteousness with lawlessness, and what communion has light with darkness. And what concord has Christ with Belial, or what part hath a believer with an unbeliever … Therefore come out from among them, and be ye separate … Having therefore these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from all filthiness of flesh and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God."[79]

The passage interrupts the flow between 6:13 and 7:2, uses a chain of scriptural citations, and contains unusual vocabulary, including the form "Beliar." Many commentators regard 6:14–7:1 as a non-Pauline insertion into a letter that itself shows composite features.[85][86]

Romans 13:1–7

[edit]"Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation. For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same: For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil. Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake. For for this cause pay ye tribute also: for they are God's ministers, attending continually upon this very thing. Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour."[79]

This well known paragraph on submission to governing authorities has also been proposed as an interpolation. Arguments cite abrupt topic shift, tensions with imminent eschatology, and vocabulary contrasts with surrounding material.[87][88]

Charles Cranfield and Robert Jewett defend authenticity on historical and rhetorical grounds and read the passage as a pastoral admonition addressed to specific Roman circumstances.[89][90]

Romans 16 and the movable doxology

[edit]"Now to him who is able to establish you according to my gospel and the preaching of Jesus Christ, according to the revelation of the mystery which was kept secret since the world began but now has been made manifest, and by the prophetic Scriptures has been made known to all nations, according to the commandment of the everlasting God, for obedience to the faith—to God, alone wise, be glory through Jesus Christ forever. Amen."[79]

Although not usually labeled an interpolation, the transmission of Romans displays recensional features. The doxology (16:24-27) is sometimes called "movable" because ancient manuscripts place it in different locations: either after 14:23, after 15:33, or at the end of chapter 16. Several early witnesses attest shorter forms that likely arose during collection and liturgical reading rather than from Paul himself.[91][92]

Forgeries

[edit]Mainstream introductions distinguish between the undisputed letters and those that are disputed or widely viewed as pseudonymous. The Pastoral Epistles (1–2 Timothy, Titus) are judged pseudonymous by most critical scholars since they presuppose advanced church structures, use distinctive vocabulary, and reflect trajectories later than Paul's lifetime.[93] Ephesians and Colossians are disputed, with many arguing for a post-Pauline author who reuses Pauline material.[94] 2 Thessalonians is also disputed for eschatological and stylistic reasons, although a substantial minority defends Pauline authorship.[95] Ehrman frames the broader issue with the claim that Christian literature includes "falsely attributed and forged writings," and that "a fair critical consensus holds" several New Testament letters are pseudonymous.[96]

Colossians

[edit]Many scholars including Eduard Lohse, Raymond E. Brown, and Udo Schnelle judge Colossians to be a post-Pauline composition. They point to an unusually dense cluster of hapax legomena, a more realized eschatology in which believers are already raised with Christ, and a cosmic Christology that reads like a developed hymn in 1:15–20. They also note a different treatment of the church and of household order, which together create a profile that stands at some distance from the argumentative style of the undisputed letters.[97][66][5] Ephesians appears to reuse and expand material from Colossians, which supports the view that Colossians belongs to a Pauline school that reworked traditional material for new audiences.[98] Defenders of authenticity argue that the different situation in the Lycus Valley, the presence of Timothy as coauthor, and the use of an amanuensis can account for the stylistic and thematic profile.[99][100][21] If the letter is pseudonymous, many date it near the end of the first century and place it within a Pauline circle that stabilized and reapplied Paul’s language to counter local teaching in Colossae.[66][5]

2 Thessalonians

[edit]The authenticity of 2 Thessalonians is disputed by scholars including Brown, Schnelle, Paul Foster, and Bart D. Ehrman. Arguments for pseudonymity note the letter's close imitation of 1 Thessalonians, its reworked eschatology with new apocalyptic detail about the man of lawlessness, and the self-referential signature claim in 3:17, which some read as a later attempt to police forged letters in Paul's name. Stylistic differences and a stronger emphasis on lawlessness and tradition are also cited.[66][5][101] Early use and reception are clear, and several major commentators including Charles A. Wanamaker, Abraham J. Malherbe, and Gene L. Green defend authenticity on the grounds that the letter addresses a new pastoral phase in the same community and adapts rhetoric rather than reversing Pauline convictions.[102][103][104] If pseudonymous, proposals cluster between 80 and 100 CE and take the letter as a corrective that reins in speculative eschatology while invoking Pauline authority.[5][105]

Ephesians

[edit]Ephesians is widely regarded as pseudonymous by critical scholars like Brown, Schnelle, and Andrew T. Lincoln, although scholars such as Harold Hoehner, Clinton E. Arnold, and David A. deSilva defend Pauline authorship. The addressee phrase in 1:1 lacks "in Ephesus" in early witnesses, which supports the view that the work circulated as a general letter. The style features long periodic sentences, distinctive vocabulary, and a hymnic tone. The ecclesiology centers on a universal church with Christ as head, and extensive overlap with Colossians suggests literary dependence that many judge to be derivative rather than source.[106][107][66][5] Others defend authenticity by appealing to secretarial mediation, the circular-letter format that explains minimal personal detail, and Paul's capacity for elevated liturgical prose.[8][108][109] On a pseudonymous reading, the letter is dated to the late first century and framed as a synthesis of Pauline themes for a network of churches that already read collections of Paul's letters.[106][5]

The Pastorals

[edit]Modern introductions typically date 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus between 100 and 150 CE, note that they were absent from Marcion's ten-letter canon around 140 CE, and observe that Irenaeus provides the earliest explicit citations, evidence that situates the collection in the post-Pauline era.[110][111] Norman Perrin summarizes the dominant critical objections, highlighting second-century vocabulary, a meditative literary style, an itinerary that cannot be reconciled with the undisputed letters, and what he calls the ethos of "emergent Catholicism," while Werner G. Kummel underscores the use of vaticinium ex eventu warnings about false teachers and the emphasis on preserving tradition through defined offices as features of a sub-apostolic church.[112][113]

1 Timothy

[edit]Scholars like P.N. Harrison, Brown, and Schnelle judge 1 Timothy to be pseudonymous. The letter presupposes developed church offices and procedures, it addresses a managed list of widows, and it combats false teaching with formulas that present "the faith" as a deposit to be guarded. The vocabulary and style differ from the undisputed letters, and the travel notices are hard to place in the known Pauline chronology.[114][66][5] Evangelical and confessional commentators like George W. Knight III, Luke Timothy Johnson, and William D. Mounce defend Pauline authorship by positing post-Acts travels, by appealing to secretarial help, and by reading the church structures as nascent rather than late.[7][115][116] On a pseudonymous view, 1 Timothy is conservatively dated between 80 and 120 CE and read as a second generation attempt to secure teaching and conduct in the wake of Pauline mission.[66][5]

2 Timothy

[edit]2 Timothy presents itself as a moving personal farewell, with Paul speaking of his "departure" (4:6), asking Timothy to "come before winter" (4:21), and lamenting that "all who are in Asia turned away from me" (1:15). Scholars like Brown and Schnelle see features of the ancient testament genre, a strong emphasis on example and endurance, and a cluster of non-Pauline terms. The profile and chronology again diverge from the undisputed letters, which supports a pseudonymous verdict in much modern scholarship.[66][5] Defenders answer that the letter's tone and unique vocabulary fit a final communication in extreme conditions and that a secretary could have shaped expression without falsifying authorship.[7][117][118] If pseudonymous, proposed dates resemble those for 1 Timothy and reflect the needs of Pauline communities that continued to write in Paul's voice.[5]

Titus

[edit]Titus provides detailed instructions for "ordaining elders" (1:5) and "sound doctrine" (2:1) in Cretan churches, while including a "faithful saying" (3:8) about household conduct. The vocabulary, attention to offices, and polemic against false teachers align with a post-Pauline setting in the judgment of many scholars. The travel notices do not fit securely into Acts or the undisputed letters.[66][5] Commentators like Knight, Philip H. Towner, and Mounce defend authenticity with the same appeals used for 1 and 2 Timothy, and they read the letter as situational guidance for a co-worker empowered to finish Paul's work on Crete.[7][119][120] On a pseudonymous reading, Titus is dated to the late first or early second century, composed within a Pauline school to consolidate church life and teaching on a new mission frontier.[5]

Hebrews

[edit]Hebrews is anonymous and is not by Paul according to modern consensus, yet some early collections, including P46, place Hebrews among Paul's letters. Origen already remarked that "who wrote the epistle, God knows," while allowing that the ideas were genuinely Pauline.[121][122] The placement of Hebrews in P46 illustrates how the Pauline corpus functioned as a publishing container before authorial attributions were standardized.[123]

Apocrypha

[edit]Early Christian literature outside the canon contains numerous writings presented as Pauline. Ancient authors often recognized these as later compositions, and modern scholarship treats them as pseudepigrapha. Motives for Pauline pseudepigraphy ranged from doctrinal defense and pastoral exhortation to the reuse of Pauline authority in new controversies, and many of these compositions imitate Pauline openings, closings, and turns of phrase in order to sound apostolic.[124]

| Part of a series on |

| New Testament apocrypha |

|---|

|

|

|

Third Corinthians

[edit]Third Corinthians is an anti-Gnostic exchange preserved with the Acts of Paul. It circulated independently, was included for a time in the Armenian Apostolic tradition, and is generally dated to the second century. The text survives in multiple languages including Greek, Latin, Coptic, and Armenian.[125][126][127] The work answers a Corinthian letter that lists teachings later identified with docetic and dualist groups, including denial that the world was made by the high God, rejection of the prophets, and denial that Christ truly suffered and rose bodily. Paul replies with emphatic affirmations of creation, incarnation, and resurrection, and he instructs the Corinthians to avoid false teachers. The exchange probably originated in a milieu that reused Pauline authority to police boundaries against emerging Gnostic theologies.[128] In the Armenian tradition the letters circulated with the Acts of Paul, were copied in biblical codices, and for centuries were read and cited as Pauline before a later consensus removed them from Armenian canonical lists.[129]

Epistle to the Laodiceans

[edit]The Latin Epistle to the Laodiceans appears in many medieval Vulgate manuscripts. It is a brief patchwork of Pauline phrases and is universally regarded as pseudepigraphal. There is no early Greek witness to this Latin text.[130][131] The composition paraphrases and stitches together sentences from canonical letters, especially Philippians, Galatians, and Ephesians. Medieval copies often place it between Colossians and 1 Thessalonians, likely in response to Colossians 4:16 which mentions a letter from Laodicea. Modern surveys of the Vulgate tradition trace widespread but uneven manuscript attestation from the early medieval period, with versions that show minor local edits and harmonizations.[131][130]

J. K. Elliott notes that many Vulgate manuscripts include Laodiceans and that medieval readers used it devotionally until humanist and post-Tridentine critics dismissed it on philological and historical grounds. Adolf von Harnack highlights the title's presence in Marcion's Apostolikon as a label for Ephesians, which shows how fluid letter titles in early Pauline collections later became reified as independent compositions that modern critics then rejected.[131][130][18]

Correspondence of Paul and Seneca

[edit]The Latin Correspondence of Paul and Seneca is a fourth-century exchange of fourteen short letters between Paul and Seneca the Younger. It was known to Jerome and Augustine. Stylistic mismatch and historical errors lead scholars to reject Pauline authorship and to date the collection several centuries after Paul and Seneca.[132][133]

The letters consist largely of mutual compliments and brief notes about Nero's court. They presuppose a scenario in which Seneca admires Paul's wisdom and Paul praises Seneca's rhetorical skill, which reflects late antique Christian interests more than a first century setting. Arguments against authenticity include un-Pauline Latin style, dependence on later Christian phraseology, anachronistic references to the stature of the Christian movement at Rome, and errors in chronology that do not fit what is known of Paul's and Seneca's lives.[134][135]

Claude W. Barlow shows how medieval readers used it to display supposed harmony between apostolic piety and Stoic morality. Joseph B. R. L. Boyle's modern collection rejects authenticity on stylistic and historical grounds yet treats the dossier as important evidence for Christian classicism and late antique forgery, analyzing its rhetorical aims in fourth century Roman settings.[136][137]

Epistle to the Alexandrians

[edit]

A letter "to the Alexandrians" appears in the Muratorian fragment as a spurious work composed under Paul's name and associated with Marcionite circles. The text itself is lost, and the fragment is the primary witness to its existence.[138] Because the letter has not survived, proposals about its content remain tentative. Adolf von Harnack suggested that the title reflects a Marcionite redactional practice of retitling known letters, while critics such as J.K. Elliott and H.A.G. Houghton judge that the fragment refers to otherwise unknown compositions used to advance a particular theological program. In the absence of text, both possibilities remain hypotheses.[139]

Acts of Paul and Thecla and the Acts of Paul

[edit]The broader Acts of Paul and Thecla cycle is part of the Acts of Paul, a second-century narrative that circulated under Paul's name. Tertullian reports that its author, a presbyter in Asia, admitted composing it "out of love for Paul," and church authorities removed him from office.[140][141] The Acts of Paul survives in Greek and in a range of versions, including Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Ethiopic, which points to wide diffusion. The Thecla episodes narrate the conversion of a young woman who embraces celibacy after hearing Paul, resists marriage under pressure from family and civic authorities, survives attempted martyrdom by fire and by beasts, and in some recensions baptizes herself in a pool of seals. Scholars read the work as a defense of female asceticism and itinerant preaching that adapts Pauline themes to late second century debates about marriage and authority.[142][143] The narrative helped sustain the cult of Thecla at Seleucia in Isauria, where late antique pilgrims venerated the saint and where hagiographic collections recorded posthumous miracles.[144]

Richard Pervo dates the Acts of Paul to the second century and reads the Thecla materials as a case study in how Pauline prestige sponsored new narratives around the canonical letters. Scholars note that the cycle circulated in Greek, Syriac, and Coptic and inspired female ascetic ideals that shaped martyrdom and missionary imaginaries.[145][146]

Apocalypse of Paul

[edit]The popular Apocalypse of Paul or Visio Pauli is a third- to fourth-century tour of heaven and hell framed as a Pauline revelation. It survives in many languages and influenced medieval visionary literature. Modern editions and studies trace its complex transmission and divergent recensions.[147][148] The standard Latin prologue claims that the book was found at Tarsus in a marble chest, a literary device that authorizes revelation by discovery and that resembles similar apocryphal prefaces. The work exists in short and long recensions and in a wide range of versions, including Greek, Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian, Old Church Slavonic, and Old Irish. It shaped the medieval imagination of the afterlife by supplying detailed punishments and tours that influenced later visionary texts and homiletic collections. Historians usually date the composition to the later fourth century, and they track its reception in monastic settings and in western vernacular adaptations.[149][150]

J. K. Elliott describes how the Visio Pauli circulated in multiple languages and shaped Western visionary literature with its structured tour of heaven and hell. Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta maps the complex family of recensions and traces the text's transmission into medieval vernaculars while noting its influence on later Christian depictions of the afterlife.[151][152]

Coptic Apocalypse of Paul

[edit]

The Gnostic Apocalypse of Paul in Nag Hammadi Codex V presents an ascent through ten heavens as an expansion of 2 Corinthians 12:2–4. It is distinct from the Latin Visio Pauli and reflects Valentinian themes.[153][154] Scholars date the work to the third century, with a Greek original later translated into Coptic. Its ascent narrative charts the soul's progress through cosmic toll houses and seats of judgment, it distinguishes psychic from pneumatic believers, and it deploys Valentinian terminology to critique lower rulers and to elevate revealed knowledge. The surviving witness in NHC V,2 confirms a developed transmission independent of the Latin Visio Pauli, even though both traditions draw on 2 Corinthians 12.[153][155]

James M. Robinson's edition presents the Nag Hammadi text as a Valentinian reworking of Paul's ascent with no evidence of liturgical use in catholic churches. Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta treats it as a resource for mapping second century Gnostic cosmology and exegesis of 2 Corinthians 12, focusing on its heaven tours and esoteric instructions rather than on any historical link to Paul.[153][154]

Prayer of the Apostle Paul

[edit]The brief Prayer of the Apostle Paul opens Nag Hammadi Codex I. It presents an esoteric invocation attributed to Paul. Scholars treat it as a later Gnostic composition that adopts Pauline prestige rather than as a historical Pauline prayer.[156][157] The work is only a few lines long in Coptic, likely translated from a Greek original, and it addresses a transcendent deity with technical epithets that recur in other Gnostic prayers. In Codex I the prayer stands as a programmatic preface to tractates that develop revelatory knowledge, which suggests a liturgical or paratextual function within the codex as copied in late antique Egypt.[158][156]

James M. Robinson publishes the short invocation at the head of the Jung Codex and reads it as a Gnostic prayer that borrows Pauline naming for authority. Marvin Meyer notes the lack of patristic citation or canonical advocacy and treats the piece as a specimen of esoteric devotion rather than evidence for historical Pauline piety.[156][157]

Critical and theological scholarship

[edit]Contemporary critical study of Pauline literature treats interpolation and pseudepigraphy as overlapping textual phenomena, with Ehrman using forgery to describe what many call pseudepigraphy. W. O. Walker Jr. synthesizes internal indicators, manuscript placement, and thematic discontinuities to identify disputed units, while Kurt Aland documents marginal sigla and the relocation of passages such as the Romans doxology as evidence that copyists themselves weighed authenticity during transmission.[159][160] Bart D. Ehrman frames ancient forgery as a contested moral category and surveys how accusations of deceit shaped early Christian debates over Pauline attribution.[161]

Harry Y. Gamble reconstructs the second-century editing of Pauline collections, tracing how compilers sequenced letters, reassigned addressees such as the so-called Laodiceans, and rejected titles tied to Marcionite circles when establishing public reading lists. Ehrman extends the analysis to forged dossiers like the Acts of Paul and Third Corinthians, arguing that they deployed Pauline prestige in doctrinal contests and that later catalogues neutralized them through marginal cautions or exclusion.[162][163]

Raymond E. Brown and Udo Schnelle report the mainstream view that Ephesians, Colossians, and 2 Thessalonians remain disputed, while the Pastoral Epistles are widely judged pseudonymous. Conservative interpreters such as George W. Knight III and David A. deSilva counter that secretarial collaboration, audience shifts, and early reception support Pauline authorship and should weigh heavily in historical judgment.[164][165][166][167]

Methodologically, Bruce W. Longenecker observes that the textual and historical tools honed in secular institutions are now common in confessional seminaries, producing wide agreement on investigative procedure even when conclusions diverge. Within those confessional conversations, Bruce M. Metzger distinguishes canonical authority from authorship verdicts, noting that Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and mainline Protestant theologians often affirm the canon on grounds of ecclesial reception while engaging critical scholarship on authorship and redaction.[168][169]

Confessional and ecclesial theologians advance counterarguments; Donald Guthrie defends Pauline authorship across the disputed letters[170], and William D. Mounce offers a line-by-line case for authentic authorship of the Pastoral Epistles, with Andreas J. Köstenberger's review in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society commending the commentary's thoroughness, linguistic analysis, and conservative stance while registering specific points of disagreement.[171][172] Terry Wilder argues that a Christian pseudonymous letter would constitute intentional deception.[173] Michael J. Kruger marshals patristic precedents, such as Tertullian's condemnation of the Acts of Paul and Serapion's rejection of the Gospel of Peter, to show that churches excluded works they judged inauthentic.[174] D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo note that no church father knowingly accepted a pseudonymous text into the canon.[175] Stanley E. Porter contends that canonical decisions relied on recognized authorship even when secretarial collaboration shaped composition.[176]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199928033

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 0385247672

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (PDF) (2nd ed.), Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and United Bible Societies, pp. 500–501

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 408–409, 456–463, 610–644

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Udo Schnelle (1998), The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 41–47, 274–283

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford University Press, pp. 48, 177, 633

- ^ a b c d George W. Knight III (1992), The Pastoral Epistles, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 20–26

- ^ a b c d David A. deSilva (2022), Ephesians, New Cambridge Bible Commentary, New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 29

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 251–312

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, pp. 48, 633,

making a false authorial claim; a form of lying

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, p. 177,

falsely attributed and forged writings; a fair critical consensus holds

- ^ a b Adolf Deissmann (1910), Light from the Ancient East, London: Hodder and Stoughton

- ^ a b Harry Y. Gamble (1975), "The Redaction of the Pauline Letters and the Formation of the Pauline Corpus", Journal of Biblical Literature, 94 (3): 403–418

- ^ a b David Trobisch (2000), The First Edition of the New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Benjamin P. Laird (2022), The Pauline Corpus in Early Christianity: Its Formation, Publication, and Circulation, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Academic

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (PDF), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 305–307

- ^ a b c Adolf von Harnack (1990), Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God, Durham, NC: Labyrinth Press, pp. 49–60

- ^ Richard I. Pervo (2014), The Acts of Paul: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Salem, OR: Polebridge

- ^ H. A. G. Houghton (2016), The Latin New Testament: A Guide to Its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 118–126

- ^ a b c E. Randolph Richards (2004), Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition and Collection, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, pp. 169–198

- ^ W. O. Walker, Jr. (2001), Interpolations in the Pauline Letters, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.), Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and United Bible Societies, pp. 500–501, 532–533

- ^ Victor Paul Furnish (2008), II Corinthians, Anchor Yale Bible 32A, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 371–383

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1977), The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford University Press, pp. 29–51, 177

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 251–312

- ^ Benjamin P. Laird (2022), The Pauline Corpus in Early Christianity: Its Formation, Publication, and Circulation (PDF), Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Academic, ISBN 9781683074212

- ^ Chester Beatty Library (1936), Biblical Papyri III (PDF), pp. 9–12

- ^ Harold W. Attridge (1989), Hebrews: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Philadelphia: Fortress, pp. 1–3

- ^ Jason D. BeDuhn (2012), "The Myth of Marcion as Redactor" (PDF), Journal of Early Christian Studies, 20 (1): 21–35

- ^ Tertullian (1964), "17", in Ernest Evans (ed.), De Baptismo, London: SPCK

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1977), The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

- ^ F. F. Bruce (1985), Romans, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, InterVarsity Press, pp. xx–xxi

- ^ Margaret E. Thrall (2004), The Second Epistle to the Corinthians, International Critical Commentary, vol. 1, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, pp. 1–20

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, Clarendon Press, p. 131

- ^ Jonathon Lookadoo (2019), "Ignatius of Antioch and Scripture", Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum / Journal of Ancient Christianity, 23 (2): 201–227, doi:10.1515/zac-2019-0012

- ^ Jonathon Lookadoo (2017), "Polycarp, Paul, and the Letters to Timothy", Novum Testamentum, 59 (4): 366–383, doi:10.1163/15685365-12341574

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (PDF), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 305–307

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (PDF), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 305–307

- ^ a b c Chester Beatty Library (1936), Biblical Papyri III (PDF), pp. 9–12

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 408–409

- ^ F. C. Baur (1875), Paul, the Apostle of Jesus Christ, London: Williams and Norgate

- ^ Stephen Neill; N. T. Wright (1988), The Interpretation of the New Testament 1861–1986, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 79–118

- ^ J. B. Lightfoot (1865), Saint Paul's Epistle to the Galatians, London: Macmillan, pp. vii–xv

- ^ Kurt Aland; Barbara Aland (1989), The Text of the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 1–15, 280–307, ISBN 9780802836113

- ^ Stephen Neill; N. T. Wright (1988), The Interpretation of the New Testament 1861–1986, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 118–147

- ^ Larry W. Hurtado (2006), The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 43–87

- ^ Wilhelm Bousset (1970), Kyrios Christos, translated by John E. Steely, Nashville: Abingdon, pp. 1–14

- ^ Rudolf Bultmann (1951), Theology of the New Testament, New York: Scribner, pp. 1–33

- ^ P. N. Harrison (1921), The Problem of the Pastoral Epistles, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ George W. Knight III (1992), The Pastoral Epistles, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 20–26

- ^ Ernst Käsemann (1971), Perspectives on Paul, Philadelphia: Fortress Press

- ^ Hans Dieter Betz (1979), Galatians, Hermeneia, Philadelphia: Fortress

- ^ Margaret M. Mitchell (1991), Paul and the Rhetoric of Reconciliation, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox

- ^ Richard B. Hays (1989), Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul, New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ Stanley K. Stowers (1986), Letter Writing in Greco-Roman Antiquity, Philadelphia: Westminster Press

- ^ Anthony Kenny (1986), A Stylometric Study of the New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ Krister Stendahl (1963), "The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West", Harvard Theological Review, 56 (3): 199–215

- ^ E. P. Sanders (1977), Paul and Palestinian Judaism, Philadelphia: Fortress Press

- ^ James D. G. Dunn (1983), "The New Perspective on Paul", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 65 (2): 95–122

- ^ N. T. Wright (2013), Paul and the Faithfulness of God, London: SPCK

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1995), Books and Readers in the Early Church, New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ E. Randolph Richards (2004), Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition and Collection, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, pp. title page, 48, 633,

use of literary deceit; making a false authorial claim; a form of lying

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 408–409, 610–644

- ^ a b Jermo van Nes (2018), "Missing 'Particles' in Disputed Pauline Letters? A Question of Method", Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 40 (3): 383–398, doi:10.1177/0142064x18755907

- ^ Harold W. Attridge (1989), Hebrews: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Philadelphia: Fortress, pp. 1–3

- ^ Andrew T. Lincoln (1990), Ephesians, Word Biblical Commentary 42, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, pp. lv–lxiii

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (PDF) (2nd ed.), Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and United Bible Societies, pp. 532–533

- ^ Candida R. Moss (2023), "The Secretary: Enslaved Workers, Stenography, and the Production of Early Christian Literature", The Journal of Theological Studies, 74 (1): 20–56, doi:10.1093/jts/flad001

- ^ Bruce W. Longenecker (2020), The New Cambridge Companion to St. Paul, Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–11

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1975), "The Redaction of the Pauline Letters and the Formation of the Pauline Corpus", Journal of Biblical Literature, 94 (3): 403–418

- ^ Benjamin P. Laird (2022), The Pauline Corpus in Early Christianity: Its Formation, Publication, and Circulation, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Academic

- ^ David Trobisch (2000), The First Edition of the New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.), Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and United Bible Societies, pp. 500–501

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1977), The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 408–409

- ^ a b c d e The Holy Bible, King James Version (Standard text of 1769 ed.), Oxford University Press

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (PDF) (2nd ed.), Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and United Bible Societies, pp. 500–501

- ^ Gordon D. Fee (1987), The First Epistle to the Corinthians, NICNT, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 694–710

- ^ Philip B. Payne (2017), "Vaticanus Distigme Obelos Symbols Marking Added Text, Including 1 Corinthians 14.34–35", New Testament Studies, 63 (4): 604–625, doi:10.1017/S0028688517000178

- ^ Birger A. Pearson (1971), "1 Thessalonians 2:13–16: A Deutero-Pauline Interpolation" (PDF), Harvard Theological Review, 64 (1): 79–94

- ^ Markus Bockmuehl (2001), "1 Thessalonians 2:14–16 and the Church in Jerusalem" (PDF), Tyndale Bulletin, 52: 1–31

- ^ Victor Paul Furnish (2008), II Corinthians, Anchor Yale Bible 32A, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 371–383

- ^ Raymond F. Collins (2013), Second Corinthians (PDF), Paideia: Commentaries on the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, pp. 274–279

- ^ W. O. Walker, Jr. (2001), Interpolations in the Pauline Letters (PDF), Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 189–222, ISBN 9780567085795

- ^ James Kallas (1965), "Romans XIII 1–7: An Interpolation", New Testament Studies, 11 (4): 365–374, doi:10.1017/S0028688500016768

- ^ C. E. B. Cranfield (1975), A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, ICC, vol. 2, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, pp. 660–679

- ^ Robert Jewett (2007), Romans: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Minneapolis: Fortress, pp. 787–818

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1977), The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

- ^ F. F. Bruce (1985), Romans, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, InterVarsity Press, pp. xx–xxi

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 456–463, 610–644

- ^ Udo Schnelle (1998), The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 41–47, 274–283

- ^ Paul Foster (2012), "Who Wrote 2 Thessalonians?" (PDF), Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, 103: 259–276

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, p. 177,

falsely attributed and forged writings; a fair critical consensus holds

- ^ Eduard Lohse (1971), Colossians and Philemon, Hermeneia, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, pp. 1–16, 25–34

- ^ Margaret Y. MacDonald (2000), Colossians and Ephesians, Sacra Pagina 17, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, pp. 3–13, 21–28

- ^ James D. G. Dunn (1996), The Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. lv–lxxii

- ^ Douglas J. Moo (2008), The Letters to the Colossians and to Philemon, Pillar New Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 44–59

- ^ Paul Foster (2012), "Who Wrote 2 Thessalonians?" (PDF), Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, 103: 259–276

- ^ Charles A. Wanamaker (1990), The Epistles to the Thessalonians, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 35–44

- ^ Abraham J. Malherbe (2000), The Letters to the Thessalonians, Anchor Yale Bible 32B, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 366–378

- ^ Gene L. Green (2002), The Letters to the Thessalonians, Pillar New Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 25–34

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, pp. 182–191

- ^ a b Andrew T. Lincoln (1990), Ephesians, Word Biblical Commentary 42, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, pp. lv–lxiii

- ^ Ernest Best (1998), A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Ephesians, International Critical Commentary, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, pp. 1–30

- ^ Harold W. Hoehner (2002), Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, pp. 2–14

- ^ Clinton E. Arnold (2010), Ephesians, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, pp. 23–33

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, p. 668

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 130–135

- ^ Norman Perrin; Dennis C. Duling (1982), The New Testament: An Introduction, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp. 264–265

- ^ Werner G. Kummel (1975), Introduction to the New Testament, translated by A. J. Mattill Jr., Nashville: Abingdon Press, pp. 379–384

- ^ P. N. Harrison (1921), The Problem of the Pastoral Epistles, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ Luke Timothy Johnson (2001), The First and Second Letters to Timothy, Anchor Bible 35A, New York: Doubleday, pp. 55–67

- ^ William D. Mounce (2000), Pastoral Epistles, Word Biblical Commentary 46, Nashville: Thomas Nelson, pp. lxiii–lxxiv

- ^ Luke Timothy Johnson (2001), The First and Second Letters to Timothy, Anchor Bible 35A, New York: Doubleday, pp. 364–378

- ^ William D. Mounce (2000), Pastoral Epistles, Word Biblical Commentary 46, Nashville: Thomas Nelson, pp. 473–483

- ^ Philip H. Towner (2006), The Letters to Timothy and Titus, New International Commentary on the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 671–678

- ^ William D. Mounce (2000), Pastoral Epistles, Word Biblical Commentary 46, Nashville: Thomas Nelson, pp. lxiii–lxxiv, 569–575

- ^ Harold W. Attridge (1989), Hebrews: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Philadelphia: Fortress, pp. 1–3

- ^ Eusebius (1926), Ecclesiastical History, vol. 2, translated by Kirsopp Lake, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 75–77

- ^ Chester Beatty Library (1936), Biblical Papyri III (PDF), pp. 9–12

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford University Press, pp. 29–51

- ^ J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 288–296

- ^ Vahan Hovhanessian (2000), Third Corinthians: Reclaiming Paul for Christian Orthodoxy, New York: Peter Lang

- ^ M. H. Scharlemann (1955), "Third Corinthians", Concordia Theological Monthly, 26: 161–173

- ^ J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 288–296

- ^ Vahan Hovhanessian (2000), Third Corinthians: Reclaiming Paul for Christian Orthodoxy, New York: Peter Lang, pp. 9–33, 97–118

- ^ a b c J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 543–546

- ^ a b c H. A. G. Houghton (2016), The Latin New Testament: A Guide to Its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts (PDF), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 118–126

- ^ Joseph B. R. L. Boyle, ed. (2017), Paul and Seneca in Dialogue (PDF), Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–12

- ^ Claude W. Barlow (1938), Epistolae Senecae ad Paulum et Pauli ad Senecam, Rome: American Academy in Rome

- ^ Joseph B. R. L. Boyle, ed. (2017), Paul and Seneca in Dialogue, Leiden: Brill, pp. 3–10

- ^ Claude W. Barlow (1938), Epistolae Senecae ad Paulum et Pauli ad Senecam, Rome: American Academy in Rome, pp. 5–18

- ^ Joseph B. R. L. Boyle, ed. (2017), Paul and Seneca in Dialogue (PDF), Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–12

- ^ Claude W. Barlow (1938), Epistolae Senecae ad Paulum et Pauli ad Senecam, Rome: American Academy in Rome

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (PDF), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 305–307

- ^ Geoffrey M. Hahneman (1992), The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 66–73

- ^ Tertullian (1964), "17", in Ernest Evans (ed.), De Baptismo, London: SPCK

- ^ Richard I. Pervo (2014), The Acts of Paul: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Salem, OR: Polebridge

- ^ Jeremy W. Barrier (2009), The Acts of Paul and Thecla: A Critical Introduction and Commentary, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 1–24, 177–214

- ^ Richard I. Pervo (2014), The Acts of Paul: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Salem, OR: Polebridge, pp. 1–22, 95–139

- ^ Stephen J. Davis (2001), The Cult of Saint Thecla: A Tradition of Women's Piety in Late Antiquity, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–34, 110–147

- ^ Tertullian (1964), "17", in Ernest Evans (ed.), De Baptismo, London: SPCK

- ^ Richard I. Pervo (2014), The Acts of Paul: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Salem, OR: Polebridge

- ^ J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 616–641

- ^ Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (2016), "The Apocalypse of Paul (NHC V,2): Cosmology, Anthropology, and Ethics" (PDF), Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies, 1: 110–131

- ^ Jan N. Bremmer; István Czachesz, eds. (2007), The Visio Pauli and the Gnostic Apocalypse of Paul, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 1–19, 21–42

- ^ Martha Himmelfarb (1983), Tours of Hell: An Apocalyptic Form in Jewish and Christian Literature, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 89–121

- ^ J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 616–641

- ^ Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (2016), "The Apocalypse of Paul (NHC V,2): Cosmology, Anthropology, and Ethics" (PDF), Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies, 1: 110–131

- ^ a b c James M. Robinson, ed. (1988), The Nag Hammadi Library in English, San Francisco: Harper and Row, pp. 255–260

- ^ a b Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (2007), J. Bremmer and I. Czachesz (ed.), The Visio Pauli and the Gnostic Apocalypse of Paul: The Coptic Apocalypse of Paul in Ms Or 7023, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 151–174

- ^ Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (2016), "The Apocalypse of Paul (NHC V,2): Cosmology, Anthropology, and Ethics" (PDF), Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies, 1: 110–131

- ^ a b c James M. Robinson, ed. (1988), The Nag Hammadi Library in English, San Francisco: Harper and Row, pp. 30–31

- ^ a b Marvin Meyer, The Prayer of the Apostle Paul, Gnostic Society

- ^ Bentley Layton (1987), The Gnostic Scriptures, New York: Doubleday, pp. 33–35

- ^ W. O. Walker, Jr. (2001), Interpolations in the Pauline Letters, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press

- ^ Kurt Aland; Barbara Aland (1989), The Text of the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 280–307, ISBN 9780802836113

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, pp. 48, 633,

moral category

- ^ Harry Y. Gamble (1975), "The Redaction of the Pauline Letters and the Formation of the Pauline Corpus", Journal of Biblical Literature, 94 (3): 403–418

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery, Oxford University Press, pp. 48, 177, 633

- ^ Raymond E. Brown (1997), An Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, pp. 456–463, 610–644

- ^ Udo Schnelle (1998), The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 41–47, 274–283

- ^ George W. Knight III (1992), The Pastoral Epistles, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 20–26

- ^ David A. deSilva (2018), Ephesians, New Cambridge Bible Commentary, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–25

- ^ Bruce W. Longenecker (2020), The New Cambridge Companion to St. Paul, Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–11

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger (1987), The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 251–312

- ^ Donald Guthrie (1990), New Testament Introduction, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press

- ^ William D. Mounce (2000), Pastoral Epistles, Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 46, Nashville: Thomas Nelson

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger (2002), "Review of William D. Mounce, Pastoral Epistles", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 45 (3): 365–366

- ^ Terry L. Wilder (2004), Pseudonymity, the New Testament, and Deception: An Inquiry into Intention and Reception, Lanham, MD: University Press of America

- ^ Michael J. Kruger (1999), "The Authenticity of 2 Peter", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 42 (4): 646–649

- ^ D. A. Carson; Douglas J. Moo (2005), An Introduction to the New Testament (2nd ed.), Grand Rapids: Zondervan, p. 568

- ^ Stanley E. Porter (1995), "Pauline Authorship and the Pastoral Epistles: Implications for Canon", Bulletin for Biblical Research, 5: 105–123

Further reading

[edit]- Kurt Aland; Barbara Aland (1989), The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, ISBN 9780802836113

- Harry Y. Gamble (1977), The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

- Victor Paul Furnish (2008), II Corinthians, Anchor Yale Bible 32A, New Haven: Yale University Press

- Robert Jewett (2007), Romans: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Minneapolis: Fortress

- W. O. Walker, Jr. (2001), Interpolations in the Pauline Letters, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press

- J. K. Elliott (1993), The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Benjamin P. Laird (2022), The Pauline Corpus in Early Christianity: Its Formation, Publication, and Circulation, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Academic

- Bart D. Ehrman (2013), Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics, Oxford: Oxford University Press

See also

[edit]- Textual criticism of the New Testament

- Authorship of the Pauline epistles

- Pseudepigrapha

- Biblical canon

- Marcion

- Muratorian fragment

- Papyrus 46