Social mobility

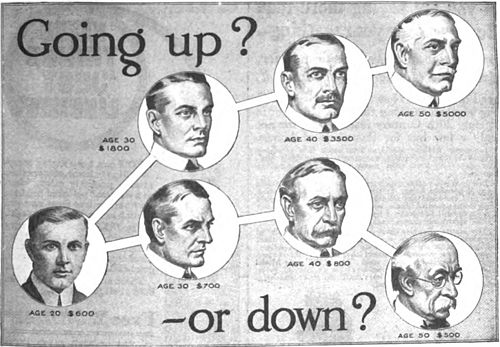

Social mobility is when people (like individuals, families, or households) move between different levels or layers, called social strata, in a society.[1] It means a person's social status changes compared to their starting place in that society. This movement happens in "open" societies. An open society is one where people can change their position, at least partly, based on what they achieve (like getting an education), not just on what they were born into. A person can move upward to a higher level or downward to a lower one.[2] Things like education and class are used as "markers" to study, predict, and learn more about a person's or group's mobility in society.

Typology

[change | change source]Mobility is most often measured using numbers (quantitatively). This usually means looking at changes in economic mobility, like changes in a person's income or wealth. A person's job (occupation) is another way to measure mobility. Studying jobs can involve both numbers and quality-based analysis. Other studies just focus on social class.[3] Mobility can happen within one person's lifetime (this is called intragenerational). It can also happen between parents and their children (called intergenerational).[4] It is less common for one person to move a long way, like in a "rags to riches" story. This is a type of upward intragenerational mobility. It is more common for children or grandchildren to have a better economic life than their parents or grandparents. This is called intergenerational upward mobility. In the US, this idea is a basic part of the "American Dream". However, the US actually has less of this mobility than most other OECD countries.[5] Mobility can also be "absolute" or "relative". Absolute mobility measures a person’s progress in areas such as education, health, housing, income, and job opportunities, comparing it to a starting point—usually the previous generation. Because of new technology and economic growth, most people's incomes and living conditions get better over time. In this "absolute" way, most people in the world, on average, are living better today than in the past. This means they have experienced absolute mobility. Relative mobility looks at a person’s movement compared to other people around them (their "cohort"). In more advanced economies and OECD countries, there is usually more room for absolute mobility than for relative mobility. For example, a person from a middle-class family might stay middle-class compared to others their age (no relative mobility). But, they will still have a better standard of living because the whole society got richer over time (absolute mobility). There is also an idea of "stickiness". This is when a person stops moving up or down compared to others. This happens most often at the very top and very bottom of the social ladder. At the bottom, parents cannot give their children the resources or opportunity to improve their lives. As a result, they stay on the same level as their parents. At the top, parents with high socioeconomic status (SES) have the resources and opportunities to make sure their children also stay at the same top level.[6] In East Asian countries, this is shown by the idea of familial karma.[1][clarification needed]

Social status and social class

[change | change source]How much social mobility exists depends a lot on the structure of social statuses and jobs in a society.[7] The number of different social positions, and how they relate to each other, creates the society's social structure. This can be complex. For example, Max Weber said status has three parts (delineation):[8] economic position (wealth), prestige (respect), and power. These parts make the social system complicated. These different parts can be studied as independent variables. They help explain why social mobility is different in different times and places. Other things also affect social mobility, just as they affect income, social status, social class, and social inequality. These include a person's sex or gender, race or ethnicity, and age.[9] Education offers one of the best ways for people to move up (upward social mobility) and get a higher social status, no matter where they start. However, the way society is layered into classes and the high level of wealth inequality have a direct impact on a person's education opportunities and results. This means a family's social class and socioeconomic status directly change a child's chances of getting a good education and doing well in life. By the time they are five years old, there are already big differences in the brain skills (cognitive) and social skills (noncognitive) of children from low, middle, and upper-class families.[10]

Among older children, evidence suggests that the gap between high- and low-income primary- and secondary-school students has increased by almost 40 percent over the past thirty years. These differences persist and widen into young adulthood and beyond. Just as the gap in K–12 test scores between high- and low-income students is growing, the difference in college graduation rates between the rich and the poor is also growing. Although the college graduation rate among the poorest households increased by about 4 percentage points between those born in the early 1960s and those born in the early 1980s, over this same period, the graduation rate increased by almost 20 percentage points for the wealthiest households.[10]

Between 1975 and 2011, the average family income and social status for the poorest third of all children went down. For families at the very bottom (the 5th percentile), average family income fell by as much as 60%.[10] The wealth gap between rich and poor (upper and lower class) keeps getting wider. More middle-class people are becoming poorer, and lower-class people are becoming even poorer. As this inequality in the United States grows, a child born at the top or the bottom is more likely to stay there for their whole life.

A child born to parents with income in the lowest quintile is more than ten times more likely to end up in the lowest quintile than the highest as an adult (43 percent versus 4 percent). And, a child born to parents in the highest quintile is five times more likely to end up in the highest quintile than the lowest (40 percent versus 8 percent).[10]

One reason for this might be parenting styles. Lower- and working-class parents (where neither parent has more than a high school diploma) often spend less time on average with their young children. They may also be less involved in their children's education and free time. This style is called "accomplishment of natural growth". It is different from the style of middle- and upper-class parents (where at least one parent has higher education). Their style is called "cultural cultivation".[11] Richer (more affluent) social classes can spend more time with their young children. These children get to experience more activities and interactions that help their brains and social skills grow, such as being read to every day, parent-child engagement, and verbal communication. These parents are also more involved in their children's school work and free time. They sign them up for extracurricular activities which teach more social skills and also academic values and habits. This helps children learn to talk better with people in charge (authority figures). Having so many activities can make family life very busy ("frenetic"), with parents spending a lot of time driving children around. Lower-class children often go to schools that are not as good. They may get less attention from teachers and are less likely to ask for help than children from higher-class families.[12] A child's chance for social mobility is mostly set by the family they are born into. Today, the gaps in getting an education and succeeding in it (like graduating from college) are even larger. Today, even when college applicants from all classes are equally qualified, 75% of new students at the best American universities come from the richest fourth (quartile) of society. This leaves low-income students with less chance to do well in school and move up in society. This is partly because of the parenting style common in lower- and working-class families, which affects how children see and succeed in education.[12]

Class cultures and social networks

[change | change source]These different parts of social mobility can be sorted by different types of "capital". Cultural capital is a term from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. It separates the economic parts of class from the cultural parts. Bourdieu named three types of capital that put a person into a social category: economic capital, social capital, and cultural capital. Economic capital is money and other things you own, such as cash, credit, and other material assets. Social capital is all the resources you get from being in a group. This includes your "network" of influential people, your relationships, and the support you get from others.[13] Cultural capital is any advantage that gives a person a higher status in society. This includes education, skills, or other kinds of knowledge. Usually, people who have all three types of capital have a high status in society. Bourdieu found that upper-class culture focuses more on formal logic and abstract ideas. Lower-class culture focuses more on practical facts and the needs of daily life. He also found that the place where a person grows up has a big effect on what cultural resources they will get.[13] A person's cultural resources can have a big impact on their child's success in school. Studies show that students raised with the "concerted cultivation" style feel "an emerging sense of entitlement". This leads them to ask teachers more questions and be more active in class. As a result, teachers tend to favor students raised this way.[14] This parenting style is the opposite of the "natural growth" style. This style is more common in working-class families. In this approach, parents do not focus on building the special talents of each child. They often speak to their children using commands (directives).[14] Because of this, a child raised this way is less likely to question or challenge adults. This creates conflict between how they are raised at home and how they are expected to act at school. These children are less likely to join in classroom discussions or to try to build relationships with their teachers. However, these children also have more freedom. This gives them a wider range of local friends to play with, closer relationships with their cousins and extended family, less fighting with siblings, and fewer complaints about being bored. They also tend to argue less with their parents.[14] In the United States, some have argued that minority students do worse in school because they lack cultural, social, and economic capital. But this doesn't explain everything. "Once admitted to institutions of higher education, African Americans and Latinos continued to underperform relative to their white and Asian counterparts, earning lower grades, progressing at a slower rate and dropping out at higher rates. More disturbing was the fact that these differentials persisted even after controlling for obvious factors such as SAT scores and family socioeconomic status".[15] The "capital deficiency" theory is one of the most common explanations for why minority students underperform in school. It says that for some reason, they just do not have the resources they need to succeed.[16] Besides social, economic, and cultural capital, another big factor is human capital. This is a newer idea from social scientists. It is about a child's education and preparation for life. "Human capital refers to the skills, abilities and knowledge possessed by specific individuals".[17] This lets parents who went to college (who have a lot of human capital) invest in their children in ways that help them succeed later. This includes everything from reading to them at night to understanding the school system better. This understanding makes them less likely to just accept what teachers and schools say.[16] Research also shows that well-educated black parents have a harder time passing this human capital to their children than white parents do. This is because of the long history of racism and discrimination.[16]

Markers

[change | change source]Health

[change | change source]The "social gradient" in health is an idea that a person's health is linked to their social status. People with lower status often have worse health.[18] There are two main ideas about health and social mobility: the social causation hypothesis and the health selection hypothesis. These ideas ask: Does your health decide your social mobility? Or does your social mobility decide your health? The social causation hypothesis says that social factors determine a person's health. These factors include a person's behavior and where they live. On the other hand, the health selection hypothesis says that a person's health determines which social stratum (or level) they will end up in.[19] Much research has studied the link between socioeconomic status and health. A recent study found more evidence for the social causation hypothesis (that class determines health). That study's analysis found no support for the health selection hypothesis.[20] Another study found that support for either idea depends on how you look at the relationship. The health selection hypothesis (health determines class) seems true when looking at the job market. This might be because health affects a person's productivity and whether they can be employed. The social causation hypothesis (class determines health) seems true when looking through the "lenses" of education and income.[21]

Education

[change | change source]The way societies are layered (stratification) can stop or help social mobility. In these layered societies, education can be a tool for people to move from one level to another. However, higher education policies have often worked to create and strengthen these layers.[22] There are big gaps in the quality of education and the money invested in students between top "elite" universities and "standard" ones. These gaps are a reason for the lower upward social mobility of the middle class and the lower class. On the other hand, the upper class tends to stay at the top (it is "self-reproducing"). This is because they have the money and resources to afford, and get into, an elite university. Because they went to these schools, these students can then give the same advantages to their own children.[23] Another example is that parents with high or middle socioeconomic status can send their children to preschool or other early education programs. This improves their children's chances of doing well in school later on.[6]

Housing

[change | change source]"Mixed housing" is the idea that people from different socioeconomic statuses (rich and poor) can live in the same neighborhood. Not much research has been done on this. However, the common belief is that mixed housing could help low-income people get the resources and social connections they need to move up in society.[24] Other possible benefits could include positive changes in behavior, better sanitation, and safer living conditions for the low-income residents. This is because higher-income people are more likely to demand better quality homes, schools, and infrastructure. This kind of housing is paid for by for-profit companies, non-profit groups, and public (government) organizations.[25] However, the research that does exist shows that mixed housing does not help people move up in society.[24] Instead of building deep relationships, residents from different classes tend to just have casual talks and mostly stay separate. If this continues, it can lead to the gentrification of a community.[24] Outside of mixed housing, low-income people often feel that their relationships are more important ("salient") for their chances of moving up than their neighborhood is. This is because their income is often not enough to pay all their monthly bills, including rent. Their strong relationships with other people give them the support system they need to pay their expenses. At times, low-income families might "double up" (have more than one family live in one home) to lessen the financial burden on each family. But even this kind of support system is not enough to help them move up compared to others (upward relative mobility).[26]

Income

[change | change source]

Economic and social mobility can also be seen as following the Great Gatsby curve. This curve shows that when a society has high levels of economic inequality (a big gap between rich and poor), it also has low rates of relative social mobility (it's harder for people to move up). The reason for this might be "Economic Despair". This idea says that when the gap between the poor and the middle class gets too big, people at the bottom are less likely to invest in themselves (like getting an education, or "human capital"). This is because they lose hope in their ability to move up and stop believing they have a fair chance. An example of this can be seen in education, especially with high school drop-outs. Students from low-income families might stop seeing a reason to invest in their education if they keep failing to improve their social position.

Race

[change | change source]Race has been a factor in social mobility since colonial times.[28] People have discussed whether race still makes it harder for a person to move up, or if social class now has a bigger effect. A study in Brazil found that racial inequality mainly existed for people who were not already in the high class. This means race affects a person's chances of moving up unless they start in the upper class. Another theory is that over time, inequality based on race will be replaced by inequality based on class.[28] However, other research has found that minorities, especially African Americans, are still watched more closely ("policed" or observed) at their jobs than their white co-workers. This constant watching has often led to African Americans being fired more often. In this situation, African Americans face racial inequality that stops them from moving up in society.[29]

Gender

[change | change source]A 2019 study in India found that Indian women have less social mobility than men. One possible reason is that girls get a poor education, or no education at all.[30] In countries like India, it is common for educated women to not use their education to move up in society. This is because of cultural and traditional customs. They are expected to become homemakers (stay at home) and let the men earn money ("bread winning").[31]

A 2017 study of Indian women found that women are often not allowed to get an education. This is because their families may think it is a better economic choice to spend money on the education and health of their sons instead of their daughters. From the parents' point of view, the son is the one who will take care of them when they are old, while the daughter will move away to live with her husband. The son will earn an income, but the daughter might need a dowry (money paid by her family) to get married.[31]

When women do join the workforce, it is very unlikely that they will be paid the same as men. Women's pay can also be different from each other because of their race.[32] To fight these gender disparities (differences), the UN made reducing gender inequality one of its Millennium Development Goals. However, some people say this goal is too general ("broad") and does not include a clear plan for action.[33]

Patterns of mobility

[change | change source]

Most people agree that some social mobility is good for a society. However, there is no agreement on "how much" mobility is best. There is no official international standard (benchmark) for social mobility. But, we can compare mobility levels between different countries or regions, or look at changes within one area over time.[35] It is possible to compare different types of economies, but comparing similar types of economies usually gives data that is easier to compare. These comparisons usually look at intergenerational mobility. They study how much a child's chances in life are affected by the family they are born into.

In a 2009 study called The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, researchers Wilkinson and Pickett studied social mobility in developed countries.[34] They found a link between high social inequality and low social mobility. (This was in addition to finding other bad social outcomes in unequal societies). Of the eight countries they studied—Canada, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the UK, and the US—the US had the most economic inequality and the least economic mobility. In this study and others, the US has very low mobility for people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. Mobility gets a little better as you go up the ladder, but then decreases again at the very top.[37] A 2006 study that compared social mobility between developed countries[38][39][40] found that the four countries with the highest social mobility were Denmark, Norway, Finland, and Canada. These countries had the lowest "intergenerational income elasticity". This means that in these countries, less than 20% of the advantages of having a rich parent were passed on to their children.[39]

A 2012 study found a "clear negative relationship" between income inequality and intergenerational mobility.[41] Countries with low levels of inequality, like Denmark, Norway, and Finland, had some of the highest mobility. The two countries with high levels of inequality—Chile and Brazil—had some of the lowest mobility.

In Britain, there has been a lot of debate about social mobility. This was sparked by comparing two studies: the 1958 National Child Development Study (NCDS Archived 2000-09-19 at the Wayback Machine) and the 1970 Birth Cohort Study (BCS70[permanent dead link]).[42] These studies compared the mobility of people's incomes between 1958 and 1970. They claimed that mobility decreased a lot in just 12 years. These findings have been controversial. This is partly because other findings on social class mobility using the same data found different results.[43] People also had questions about the data, like who was included in the study and how missing information was handled.[44] UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown famously said that trends in social mobility "are not as we would have liked".[45]

Along with the "Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults?" study, The Economist magazine also said that "evidence from social scientists suggests that American society is much 'stickier' than most Americans assume. Some researchers claim that social mobility is actually declining."[46][47] A 2006 German study confirmed these results.[48]

Even though mobility is low, in 2008, Americans had the highest belief in meritocracy (the idea that people succeed based on talent and effort) among middle- and high-income countries.[49] A 2014 study of top corporate leaders in France found that social class still influences who gets to the top. People from the upper-middle classes tend to dominate, even though France has long emphasized meritocracy.[50]

In 2014, Thomas Piketty found that in countries with low economic growth, the gap between wealth and income seems to be returning to very high levels. He said this is similar to the "classic patrimonial" wealth-based societies of the 19th century. In those societies, a small group of people (a minority) lives off their wealth, while everyone else works just to survive (subsistence living).[51]

Social mobility can also be affected by differences within the education system. The role of education in social mobility is often overlooked in research, but it has the power to change the link between where people start in life (their social origins) and where they end up (their destinations).[52] Looking at the differences in educational opportunities based on location shows how educational mobility affects social mobility. There is some debate about how important education level is. A large amount of research argues that a person's social origin has a "direct effect" (DESO) on their success, which cannot be explained just by their level of education.[53]

Other evidence suggests the opposite. This evidence says that if you measure education in enough detail (including things like which university they went to and what they studied), then education does fully explain the link between a person's social origin and getting a top-class job.[54]

In the US, the differences in educational mobility between inner-city schools and suburban schools are clear. Graduation rates show these patterns. In the 2013–14 school year, Detroit Public Schools had a graduation rate of 71%. Grosse Pointe High School, a whiter suburb of Detroit, had an average graduation rate of 94%.[55]

In 2017, a similar pattern was seen in Los Angeles, California, and in New York City. Los Angeles Senior High School (inner city) had a graduation rate of 58%, while San Marino High School (a suburb) had a graduation rate of 96%.[56] New York City Geographic District Number Two (inner city) had a 69% graduation rate, while the Westchester School District (a suburb) had an 85% graduation rate.[57] These patterns were seen all over the country when comparing inner-city and suburban graduation rates.

The economic grievance thesis is an idea about populism. It argues that big economic changes, like the loss of industry (deindustrialisation), new economic policies (economic liberalisation), and deregulation, are creating a "left-behind" group of people. This group has low job security, faces high inequality, and their wages are not growing (wage stagnation). This group then supports populism.[58][59] Some theories just focus on the effect of economic downturns (economic crises)[60] or inequality.[61] Another economic reason is the globalization happening in the world today. Populist criticism targets the growing inequality caused by the "elite," but it also targets the growing inequality among regular people caused by globalization, such as the influx of immigrants.

The evidence is clear that economic inequality and unstable family incomes are increasing, especially in the United States. This is shown in the work of Thomas Piketty and others.[62][63][64] Writers like Martin Wolf argue that economics is very important.[65] They warn that these trends make people resentful and more likely to believe populist arguments. The evidence for this is mixed. On a large scale (macro level), political scientists find that dislike of foreigners (xenophobia), anti-immigrant feelings, and anger towards "out-groups" tend to be higher during bad economic times.[62][66] Economic crises have been linked to gains for far-right political parties.[67][68] However, on a small scale (micro- or individual level), there is little evidence that individual economic problems are linked to supporting populism.[62][58] Populist politicians also tend to put pressure on the independence of central banks.[69]

Related pages

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- 1 2 "A Family Affair". Economic Policy Reforms 2010. 2010. pp. 181–198. doi:10.1787/growth-2010-38-en. ISBN 9789264079960.

- ↑ Heckman JJ, Mosso S (August 2014). "The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility" (PDF). Annual Review of Economics. 6: 689–733. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040753. PMC 4204337. PMID 25346785. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ Grusky DB, Cumberworth E (February 2010). "A National Protocol for Measuring Intergenerational Mobility" (PDF). Workshop on Advancing Social Science Theory: The Importance of Common Metrics. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Lopreato J, Hazelrigg LE (December 1970). "Intragenerational versus Intergenerational Mobility in Relation to Sociopolitical Attitudes". Social Forces. 49 (2): 200–210. doi:10.2307/2576520. JSTOR 2576520.

- ↑ Causa O, Johansson Å (July 2009). "Intergenerational Social Mobility Economics Department Working Papers No. 707". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- 1 2 "A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility - en - OECD". www.oecd.org. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- ↑ Grusky DB, Hauser RM (February 1984). "Comparative Social Mobility Revisited: Models of Convergence and Divergence in 16 Countries". American Sociological Review. 49 (1): 19–38. doi:10.2307/2095555. JSTOR 2095555.

- ↑ Weber M (1946). "Class, Status, Party". In H. H. Girth, C. Wright Mills (eds.). From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University. pp. 180–95.

- ↑ Collins, Patricia Hill (1998). "Toward a new vision: race, class and gender as categories of analysis and connection". Social Class and Stratification: Classic Statements and Theoretical Debates. Boston: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 231–247. ISBN 978-0-8476-8542-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Greenstone M, Looney A, Patashnik J, Yu M (18 November 2016). "Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ Lareau, Annette (2011). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. University of California Press.

- 1 2 Haveman R, Smeeding T (1 January 2006). "The role of higher education in social mobility". The Future of Children. 16 (2): 125–50. doi:10.1353/foc.2006.0015. JSTOR 3844794. PMID 17036549. S2CID 22554922.

- 1 2 Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-56788-6.[page needed]

- 1 2 3 Lareau, Annette (2003). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. University of California Press.

- ↑ Bowen W, Bok D (20 April 2016). The Shape of the River : Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400882793.[page needed]

- 1 2 3 Massey D, Charles C, Lundy G, Fischer M (27 June 2011). The Source of the River: The Social Origins of Freshmen at America's Selective Colleges and Universities. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400840762.

- ↑ Becker, Gary (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Kosteniuk JG, Dickinson HD (July 2003). "Tracing the social gradient in the health of Canadians: primary and secondary determinants". Social Science & Medicine. 57 (2): 263–76. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00345-3. PMID 12765707.

- ↑ Dahl E (August 1996). "Social mobility and health: cause or effect?". BMJ. 313 (7055): 435–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7055.435. PMC 2351864. PMID 8776298.

- ↑ Warren JR (2009-06-01). "Socioeconomic Status and Health across the Life Course: A Test of the Social Causation and Health Selection Hypotheses". Social Forces. 87 (4): 2125–2153. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0219. PMC 3626501. PMID 23596343.

- ↑ Kröger H, Pakpahan E, Hoffmann R (December 2015). "What causes health inequality? A systematic review on the relative importance of social causation and health selection". European Journal of Public Health. 25 (6): 951–60. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv111. PMID 26089181. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ↑ Neelsen, John P. (1975). "Education and Social Mobility". Comparative Education Review. 19 (1): 129–143. doi:10.1086/445813. JSTOR 1187731. S2CID 144855073.

- ↑ Brezis ES, Hellier J (December 2016). "Social Mobility and Higher-Education Policy". Working Papers. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 Durova AO (2013). Does Mixed-Income Housing Facilitate Upward Social Mobility of Low-Income Residents? The Case of Vineyard Estates, Phoenix, AZ. ASU Electronic Theses and Dissertations (Masters thesis). Arizona State University. hdl:2286/R.I.18092.

- ↑ "Mixed-Income Housing: Unanswered Questions". Community-Wealth.org. 2017-05-30. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ↑ Skobba K, Goetz EG (2014-10-08). "Doubling up and the erosion of social capital among very low income households". International Journal of Housing Policy. 15 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1080/14616718.2014.961753. ISSN 1949-1247. S2CID 154912878.

- 1 2 Data from Chetty, Raj; Jackson, Matthew O.; Kuchler, Theresa; Stroebel, Johannes; et al. (August 1, 2022). "Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility". Nature. 608 (7921): 108–121. Bibcode:2022Natur.608..108C. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04996-4. PMC 9352590. PMID 35915342. Charted in Leonhardt, David (August 1, 2022). "'Friending Bias' / A large new study offers clues about how lower-income children can rise up the economic ladder". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- 1 2 Ribeiro CA (2007). "Class, race, and social mobility in Brazil". Dados. 3 (SE): 0. doi:10.1590/S0011-52582007000100008. ISSN 0011-5258.

- ↑ "Quick Read Synopsis: Race, Ethnicity, and Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market: Critical Issues in the New Millennium". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 609: 233–248. 2007. doi:10.1177/0002716206297018. JSTOR 25097883. S2CID 220836882.

- ↑ "MANY FACES OF GENDER INEQUALITY". frontline.thehindu.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- 1 2 Rosenblum, Daniel (2017-01-02). "Estimating the Private Economic Benefits of Sons Versus Daughters in India". Feminist Economics. 23 (1): 77–107. doi:10.1080/13545701.2016.1195004. ISSN 1354-5701. S2CID 156163393.

- ↑ "The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap". AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ↑ "Millennium Development Goals Report 2015". 2015. Retrieved 2019-10-27.[permanent dead link]

- 1 2 Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1608190362.[page needed]

- ↑ Causa O, Johansson Å (2011). "Intergenerational Social Mobility in OECD Countries". Economic Studies. 2010 (1): 1. doi:10.1787/eco_studies-2010-5km33scz5rjj. S2CID 7088564.

- ↑ Corak, Miles (August 2013). "Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 27 (3): 79–102. doi:10.1257/jep.27.3.79. hdl:10419/80702.

- ↑ Isaacs JB (2008). International Comparisons of Economic Mobility (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2014.

- ↑ CAP: Understanding Mobility in America Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine – 26 April 2006

- 1 2 Corak, Miles (2006). "Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults? Lessons from a Cross Country Comparison of Generational Earnings Mobility" (PDF). In Creedy, John; Kalb, Guyonne (eds.). Dynamics of Inequality and Poverty. Research on Economic Inequality. Vol. 13. Emerald. pp. 143–188. ISBN 978-0-76231-350-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Financial Security and Mobility - Pew Trusts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ The Great Gatsby Curve Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Paul Krugman| 15 January 2012

- ↑ Blanden J, Machin S, Goodman A, Gregg P (2004). "Changes in intergenerational mobility in Britain". In Corak M (ed.). Generational Income Mobility in North America and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82760-7.[page needed]

- ↑ Goldthorpe JH, Jackson M (December 2007). "Intergenerational class mobility in contemporary Britain: political concerns and empirical findings". The British Journal of Sociology. 58 (4): 525–46. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00165.x. PMID 18076385.

- ↑ Gorard, Stephen (2008). "A reconsideration of rates of 'social mobility' in Britain: or why research impact is not always a good thing" (PDF). British Journal of Sociology of Education. 29 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1080/01425690801966402. S2CID 51853936. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ Clark, Tom (10 March 2010). "Is social mobility dead?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "Ever higher society, ever harder to ascend". The Economist. 29 December 2004. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Mitnik P, Cumberworth E, Grusky D (2016). "Social Mobility in a High Inequality Regime". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 66 (1): 140–183. doi:10.1177/0002716215596971. S2CID 156569226.

- ↑ Jäntti M, Bratsberg B, Roed K, Rauum O, et al. (2006). "American Exceptionalism in a New Light: A Comparison of Intergenerational Earnings Mobility in the Nordic Countries, the United Kingdom and the United States". IZA Discussion Paper No. 1938.

- ↑ Isaacs J, Sawhill I (2008). "Reaching for the Prize: The Limits on Economic Mobility". The Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Maclean M, Harvey C, Kling G (1 June 2014). "Pathways to Power: Class, Hyper-Agency and the French Corporate Elite" (PDF). Organization Studies. 35 (6): 825–855. doi:10.1177/0170840613509919. S2CID 145716192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ Piketty T (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674430006.

- ↑ Brown P, Reay D, Vincent C (2013). "Education and social mobility". British Journal of Sociology of Education. 34 (5–6): 637–643. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.826414. S2CID 143584008.

- ↑ Education, occupation and social origin : a comparative analysis of the transmission. Bernardi, Fabrizio,, Ballarino, Gabriele. Cheltenham, UK. 12 February 2024. ISBN 9781785360442. OCLC 947837575.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Sullivan A, Parsons S, Green F, Wiggins RD, Ploubidis G (September 2018). "The path from social origins to top jobs: social reproduction via education" (PDF). The British Journal of Sociology. 69 (3): 776–798. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12314. PMID 28972272. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ "DPS Graduation rates are up 6.5 percentage points over last year and 11 percentage points since 2010–11". 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "Overall Niche Grade". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "WESTCHESTER COUNTY GRADUATION RATE DATA 4 YEAR OUTCOME AS OF JUNE". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- 1 2 Norris, Pippa; Inglehart, Ronald (11 February 2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–139. doi:10.1017/9781108595841. ISBN 978-1-108-59584-1. S2CID 242313055.

- ↑ Broz, J. Lawrence; Frieden, Jeffry; Weymouth, Stephen (2021). "Populism in Place: The Economic Geography of the Globalization Backlash". International Organization. 75 (2): 464–494. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000314. ISSN 0020-8183.

- ↑ Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–206. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511492037. ISBN 978-0-511-49203-7.

- ↑ Flaherty, Thomas M.; Rogowski, Ronald (2021). "Rising Inequality As a Threat to the Liberal International Order". International Organization. 75 (2): 495–523. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000163. ISSN 0020-8183.

- 1 2 3 Berman, Sheri (11 May 2021). "The Causes of Populism in the West". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102503.

- ↑ Piketty, Thomas (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-43000-6.

- ↑ Hacker, Jacob S. (2019). The great risk shift: the new economic insecurity and the decline of the American dream (Expanded & fully revised second ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-084414-1.

- ↑ Wolf, M. (December 3, 2019). "How to reform today's rigged capitalism". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ Dancygier, RM. (2010). Immigration and Conflict in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Klapsis, Antonis (December 2014). "Economic Crisis and Political Extremism in Europe: From the 1930s to the Present". European View. 13 (2): 189–198. doi:10.1007/s12290-014-0315-5.

- ↑ Funke, Manuel; Schularick, Moritz; Trebesch, Christoph (September 2016). "Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014" (PDF). European Economic Review. 88: 227–260. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.03.006. S2CID 154426984. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ↑ Gavin, Michael; Manger, Mark (2023). "Populism and de Facto Central Bank Independence". Comparative Political Studies. 56 (8): 1189–1223. doi:10.1177/00104140221139513. PMC 10251451. PMID 37305061.

Writings on the subject

[change | change source]- Clark G (2014). The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Grusky, David B; Cumberworth, Erin (2012). A National Protocol for Measuring Intergenerational Mobility? (PDF). National Academy of Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin; Bendix, Reinhard (1991). Social Mobility in Industrial Society. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412834353.

- Matthys M (2012). Cultural Capital, Identity, and Social Mobility. Routledge.

- Maume, David J. (19 August 2016). "Glass Ceilings and Glass Escalators". Work and Occupations. 26 (4): 483–509. doi:10.1177/0730888499026004005. S2CID 145308055.

- McGuire GM (2000). "Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Networks: The Factors Affecting the Status of Employees' Network Members". Work and Occupations. 27 (4): 500–523. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.979.3395. doi:10.1177/0730888400027004004. S2CID 145264871.

- Mitnik PA, Cumberworth E, Grusky DB (January 2016). "Social mobility in a high-inequality regime". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 663 (1): 140–84. doi:10.1177/0002716215596971. S2CID 156569226.

Other websites

[change | change source]- Birdsall N, Szekely M (July 1999). "Intergenerational Mobility in Latin America: Deeper Markets and Better Schools Make a Difference". Carnegie. Archived from the original on 21 October 2005.

- The New York Times offers a graphic about social mobility, overall trends, income elasticity and country by country. European nations such as Denmark and France, are ahead of the US.